Bounded Knapsack Problem: A Deep Dive into Optimization Precision

Bounded Knapsack Problem: A Deep Dive into Optimization Precision

In the world of algorithmic decision-making, few challenges as critical and nuanced as the Bounded Knapsack Problem shape the way we solve resource allocation dilemmas. This refined variation of the classical knapsack framework introduces hard limits on item quantities, transforming theoretical models into practical tools for supply chain logistics, budget planning, and inventory management. Far beyond generic capacity constraints, the bounded version demands nuanced solutions where every unit counts—making it a vital puzzle for computer scientists and operations researchers alike.

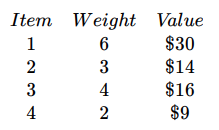

At its core, the Bounded Knapsack Problem extends the standard knapsack model by enforcing upper limits on how many of each item can be selected. Unlike the unrestricted version, where item counts are limitless, here each item type has a maximum quantity available, introducing a discrete constraint that mirrors real-world scarcity. Formally, given a set of items, each with a weight, value, and a hard cap on count, the goal is to maximize total value without exceeding knapsack capacity or item limits.

Mathematically, the problem is defined as: Maximize ∑(vᵢ·xᵢ) Subject to: ∑(wᵢ·xᵢ) ≤ W xᵢ ≤ uᵢ for all i, xᵢ ∈ ℤ≥0

where vᵢ denotes item value, wᵢ its weight, uᵢ its bounded supply, and W the total capacity. This concise formulation belies a complex optimization landscape—solving it efficiently requires sophisticated algorithms, balancing exactness with computational tractability.The challenge arises because bounded constraints fragment the solution space into discrete, interdependent choices.

Each item’s usage must respect its cap while contributing to an overall optimization objective—a dynamic tension that algorithms navigate through dynamic programming, branch-and-bound techniques, or approximation methods. This pervasive constraint makes the problem a canonical example of how bounded availability reshapes classical optimization paradigms.

From Theory to Applications: Real-World Relevance

Understanding bounded limitations is essential across domains.In manufacturing, raw materials often come in fixed batches—allocating more than permitted incurs cost or spoilage. For instance, a pharmaceutical company may have only 10,000 units of a key active ingredient, capped at each batch size; exceeding the limit disrupts production schedules and increases waste. Similarly, corporate budgeting reflects bounded knapsack principles: departments request funds within departmental caps, requiring strategic prioritization of high-impact projects.

Supply chain managers allocate truck space or container slots per shipment, where each item’s weight is constrained by physical limits. In each case, the problem reduces to selecting an optimal subset—maximizing return or utility under hard bounds.

Consider inventory planning: suppose a retailer can purchase no more than 1,000 units of product X from a single supplier.

Even if demand forecasts suggest higher needs, the bounded cap prevents overordering—driving real-time decisions on reorder levels and stock adjustments. These operational realities underscore why the bounded knapsack serves not as an abstract academic exercise but as a precision tool for day-to-day decision-making.

Core Algorithms and Computational Challenges

Solving the Bounded Knapsack Problem demands algorithms that efficiently traverse the discrete solution space. Unlike the unconstrained knapsack, which can leverage dynamic programming with value-based states, the bounded variant requires either full enumeration of allowable counts per item or optimized substructures.One foundational method is dynamic programming with bounded knapsack state transitions. For each item with supply limit uᵢ, instead of considering unlimited decrements, the algorithm iterates only over relevant counts from 0 to uᵢ. This prunes the solution space by avoiding redundant evaluations—dramatically improving performance.

For example, if an item weighs 5kg and capacity left is 50kg, processing its supply limits reduces 50 ÷ 5 = 10 checks to just 11 transitions rather than infinite expansions.

Advanced techniques include the Michael Difference Method and branch-and-bound algorithms tailored to bounded constraints. The former exploits progressive updates to the optimal value, while the latter systematically explores feasible selections, pruning branches that exceed capacity or violate limits.

Heuristic approaches like greedy strategies with local search improve scalability for large datasets but trade exactness for speed—useful in approximate solutions when precise values are secondary to timely decisions.

The problem’s computational complexity remains a key consideration. While classic knapsack runs in pseudo-polynomial time, bounded variants introduce item-dependent variable expansions that can inflate runtime.

However, modern optimizations—such as closed-form value recomputation and sparse state representations—have brought scaled solutions within practical reach for real-world instances. Studies indicate that optimized dynamic programming can handle thousands of items efficiently, making the bound sensible for enterprise-scale applications.

Case Study: Budget Allocation in Tech Startups

A compelling example emerges from startup capital management.Imagine a tech venture with a $2M investor-mandated budget, split across R&D, marketing, and operations—each with strict cap limits reflecting investor agreements and deployment urgency. The goal: maximize strategic value (e.g., innovation ROI, market reach), constrained by spending ceilings per category. Suppose: - Marketing: $800K cap, $5M value per unit efficiency - R&D: $1.2M cap, $7M value per unit - Operations: $400K cap, $1.5M value per unit With a total limit of $2M, a bounded knapsack approach determines the ideal split—say, $1.1M marketing, $700K R&D, $100K operations—to balance bounded funds with maximum impact.

Without such precision, misallocating funds risks underinvestment in high-potential zones or regulatory breaches from overspending. This mirrors broader financial planning where bounded caps dictate strategic flexibility and risk exposure.

The bounded knapsack thus becomes more than a computational puzzle: it embodies discipline in resource stewardship, ensuring finite capital powers the most value-accretive initiatives.

Optimization in Practice: Balancing Precision and Performance

In real-world deployment, choosing the right algorithmic strategy hinges on problem scale and required precision.For small-to-medium instances, full enumeration combined with dynamic programming delivers exact optimal solutions efficiently. Yet in large-scale deployments, such as logistics networks handling millions of SKUs or financial portfolios with dynamic rebalancing, approximation algorithms and heuristic frameworks offer pragmatic alternatives.

Hybrid approaches—combining exact solvers on core components with heuristic deb BufferSize usage across broader systems—emerge as best practice.

Real-time systems often demand near-optimal answers delivered within milliseconds; here, faster but approximate methods trade perfect accuracy for speed and scalability. The key lies in calibrating the balance between precision and performance to match domain constraints.

Looking Ahead: Innovation and Emerging Frontiers

As data volumes grow and decision cycles shorten, the Bounded Knapsack Problem continues evolving.Machine learning integration—using predictive models to estimate optimal caps or refine heuristic guidance—promises smarter, adaptive allocations. Quantum computing explorations hint at futures where complex bounded knapsacks resolve in exponential speedups, though practical quantum advantages remain speculative.

Equally promising is tighter coupling with constraint programming and integer linear programming frameworks, enabling richer modeling of real-world complexities—multi-period planning, probabilistic constraints, and interdependent variables.

These evolutions deepen the problem’s relevance, ensuring it remains central to optimization innovation.

At its essence, the Bounded Knapsack Problem is a microcosm of strategic decision-making under limits—a neural network of trade-offs where every unit allocated pushes toward greater efficiency. Its journey from theoretical construct to operational cornerstone reflects a broader truth: mastery over bounded resources is mastery over systems themselves.

As industries navigate tighter margins and smarter capital, this profound algorithm stands ready, still offering clarity in complexity.

Related Post

Swansea City vs Manchester City: Decoding the Lineup Showdown Between Twwarting Defenses and Tactical Precision

Experience Cinema Like Never Before: The Unmatched Magic of Fullmovieshd4K

Is Changing Everything Faster Than Expected? The Acceleration of Transformation Across Industries, Tech, and Society

How Do You Say “May I” in Spanish? The Essential Phrase You’ll Need Everyday