Catalysts: The Silent Architects That Transform Reactants into Breakthrough Products

Catalysts: The Silent Architects That Transform Reactants into Breakthrough Products

At the heart of nearly every chemical transformation lies an invisible force reshaping how materials interact: catalysts. These remarkable substances accelerate reactions between reactants without being consumed, enabling the seamless formation of products that drive innovation across industries—from pharmaceuticals to fuel production. By lowering the energy barrier required for chemical change, catalysts unlock pathways once deemed impractical or too slow for industrial application.

Their role is not merely facilitative but transformative, turning raw inputs into high-value outputs with unprecedented efficiency and sustainability. <

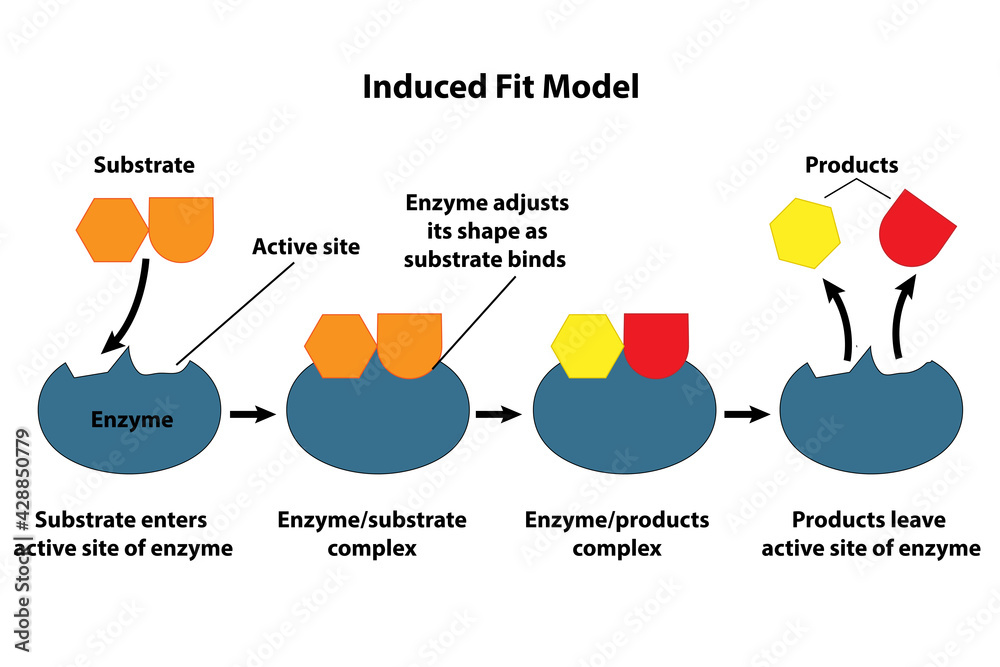

This selective interaction hinges on the catalyst’s active sites—specific molecular regions engineered to attract and orient reactants with precision. At the molecular level, the process begins when reactants collide with the catalyst surface. Often, only a fraction of these collisions result in productive reaction; catalysts dramatically increase the fraction of energetically favorable encounters.

“Catalysts serve as molecular scaffolds,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a physical chemist at the Institute of Catalytic Science. “They stabilize transition states, reducing activation energy by tens, sometimes hundreds of kilojoules per mole.

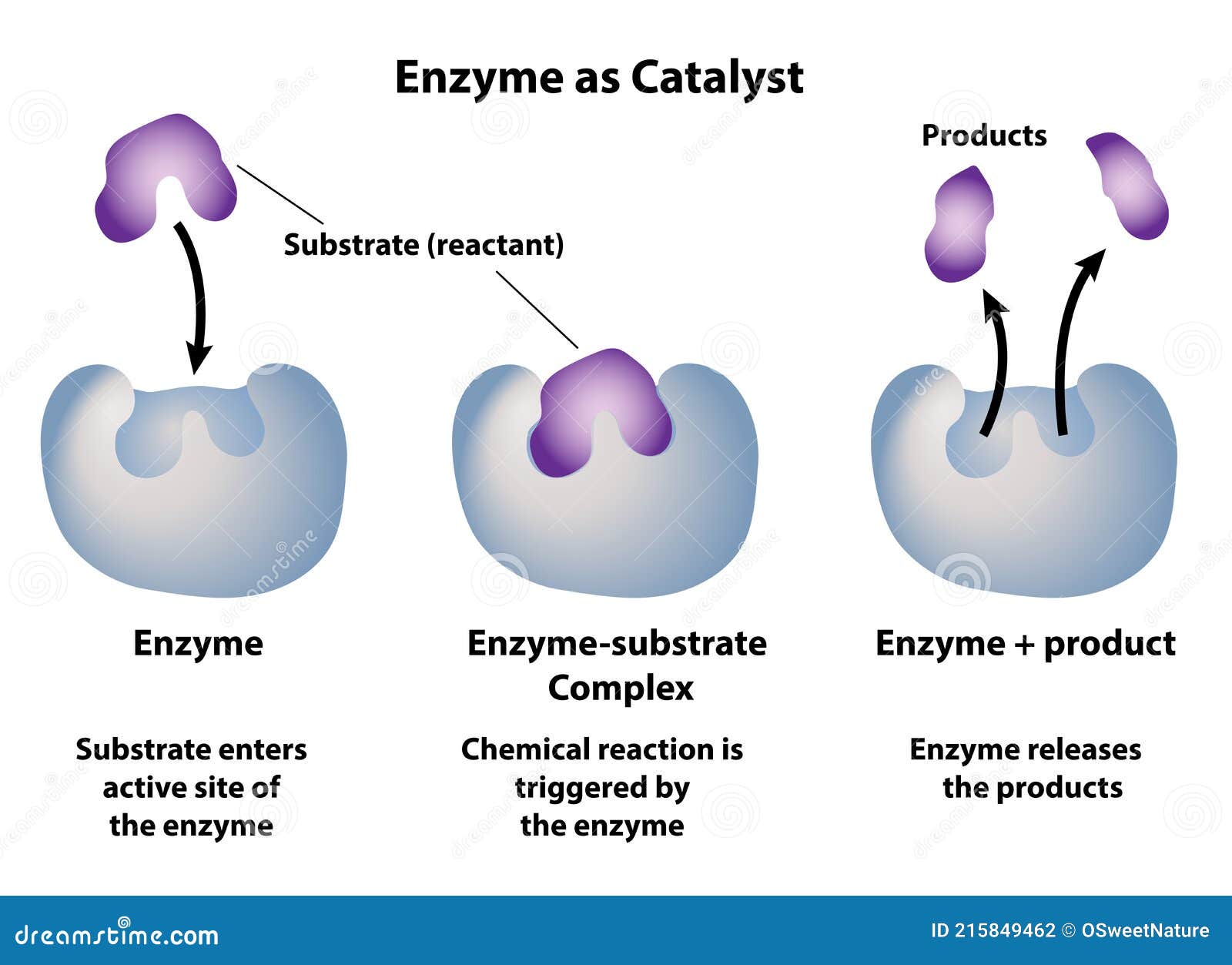

This shift enables reactions to proceed at accessible temperatures and pressures, drastically cutting energy use.” The catalytic cycle unfolds in distinct stages: - **Adsorption:** Reactant molecules bind to active sites on the catalyst. - **Reaction:** Bonds reorganize within this constrained environment, promoting transformation. - **Desorption:** The newly formed product detaches, regenerating the catalyst for another cycle.

This three-step sequence ensures repeated use, minimizing waste and maximizing output. In heterogeneous catalysis—where the catalyst differs in phase from reactants—surface chemistry dominates. Metal surfaces like platinum, palladium, or nickel provide the ideal environment for adsorption and rearrangement.

Meanwhile, homogeneous catalysts, dissolved in the same phase as reactants, offer fine-tuned control, particularly in complex organic syntheses. Scaling up catalytic processes presents both opportunity and challenge. Industrial chemists meticulously tailor catalysts to specific reactants, optimizing structure, temperature, and pressure to achieve near-perfect selectivity.

A single catalyst might favor one desired product over side products, a critical factor in reducing purification costs and environmental impact. “Selectivity isn’t just about efficiency—it’s about sustainability,” notes Dr. Raj Patel, whose group developed a novel catalyst for ammonia synthesis that cuts energy demand by over 30%.

“Wasting raw materials or generating unwanted byproducts undermines green chemistry goals.” Catalysts are not confined to traditional industrial roles. In environmental technology, catalytic converters in automobiles transform toxic exhaust gases—carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and unburned hydrocarbons—into harmless nitrogen, water, and carbon dioxide. These devices exemplify how catalysts enable cleaner, more responsible energy use.

In renewable energy, catalytic materials drive hydrogen production via water splitting, a key step toward scalable clean fuel. And in biotechnology, enzyme-based catalysts accelerate biochemical transformations, enabling efficient drug manufacturing and biosensor development. The path from locked reactants to freshly formed products reflects a profound synergy: nature’s catalysts—enzymes, for instance—have inspired synthetic analogs, leading to hybrid systems that blur the line between biology and chemistry.

Today’s catalysts are smarter, more resilient, and often self-regulating. Advances in nanotechnology produce nanoparticles with tailored surface properties, increasing active site availability and reactivity. Computational modeling accelerates catalyst discovery, predicting performance before synthesis, slashing trial-and-error timelines.

Despite their strength, catalysts face limitations. Deactivation—via poisoning, sintering, or coking—reduces efficiency over time, demanding regeneration or replacement. Researchers respond with robust materials and coatings that resist degradation.

Moreover, sourcing rare or costly metals like platinum raises sustainability concerns, spurring innovation in earth-abundant alternatives such as iron-based or carbon-based catalysts. Every industrial revolution since the 19th century has relied on catalytic breakthroughs—from Ostwald’s ammonia synthesis to modern fluid catalytic cracking in refineries. These milestones underscore catalysts not as footnotes, but as foundational forces.

They enable the production of billions of tons of materials annually: fertilizers feeding global populations, polymers shaping consumer goods, pharmaceuticals curing diseases.

From Lab Bench to Factory Floor: Catalytic Efficiency in Industrial Synthesis

Consider the Haber-Bosch process, where nitrogen and hydrogen react under extreme heat and pressure, catalyzed by iron. This reaction, responsible for synthesizing ammonia—the cornerstone of nitrogen fertilizers—transforms inert atmospheric gas into a reactive precursor used in over 100 million tons of fertilizer yearly.“Without catalysis, this reaction would be too slow and too energy-intensive to scale,” observes Dr. Maria Chen, a chemical engineer specializing in industrial catalysis. “Today’s optimized iron catalysts boost yields by more than 50% under milder conditions, directly impacting food security.” Similarly, catalysts drive the petrochemical industry.

Fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) uses zeolites—microporous aluminosilicates—to cleave long hydrocarbon chains into gasoline, diesel, and lubricants. These catalysts selectively break bonds at specific molecular sites, enabling precise control over product distribution. “FCC catalysts determine refinery profitability,” says industry expert James Liu.

“Modern variants yield up to 70% gasoline from heavy crude fractions, reducing waste and improving yield.” In pharmaceutical manufacturing, catalysts enable stepwise synthesis of complex molecules. Transition metal complexes, particularly those involving palladium, catalyze cross-coupling reactions—such as Suzuki and Heck couplings—that stitch aromatic rings into life-saving drugs. These methods reduce steps, minimize hazardous reagents, and enhance atom economy.

As pharmaceutical companies race to develop new therapies, catalytic precision becomes indispensable. The environmental impact of catalytic processes cannot be overstated. By reducing reaction temperatures and pressures,

Related Post

Catalysts: The Invisible Architects Transforming Reactants into Products

The Unmistakable Roar: Decoding the Husqvarna SM 125 4T Sound Phenomenon

John Cena Sparks Speculation with Potential Swiftie Admission

-1685429297612.jpg)