Community in Ecology: The Shifting Balance of Interdependence in Natural Systems

Community in Ecology: The Shifting Balance of Interdependence in Natural Systems

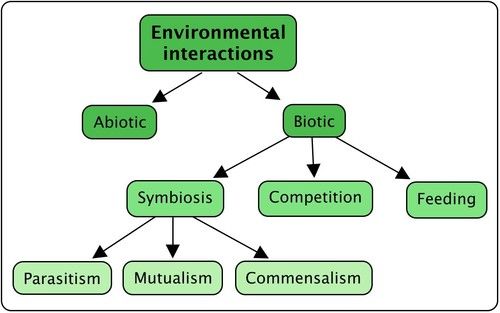

In ecosystems worldwide, the concept of “community in ecology” serves as a foundational lens through which biologists understand the complex, dynamic relationships among different species coexisting in shared habitats. This term encapsulates the intricate web of interactions—ranging from mutual cooperation and commensal tolerance to fierce competition and predation—that shape the survival, adaptation, and evolution of organisms. Far more than a simple collection of species, a freshwater insect community or a tropical rainforest canopy represents a functional network where every organism plays a role, however small, in maintaining ecological balance.

“A community is not just a group of species living in proximity,” notes ecologist Dr. Elena Martinez, “but a living, interacting system governed by interdependence and feedback loops.” At its core, the ecological community definition emphasizes that species coexist through reciprocal influences—biological, physical, and environmental. These include nutrient cycling driven by decomposers, pollination mutualisms between plants and insects, and predator-prey cycles that regulate population dynamics.

The structure and function of these communities depend heavily on species diversity and the stability of key interactions. When a single species is lost—whether due to habitat destruction, climate change, or invasive species—the consequences often ripple through the community, altering food webs and reducing resilience.

The Components of Ecological Communities: Species and Their Roles

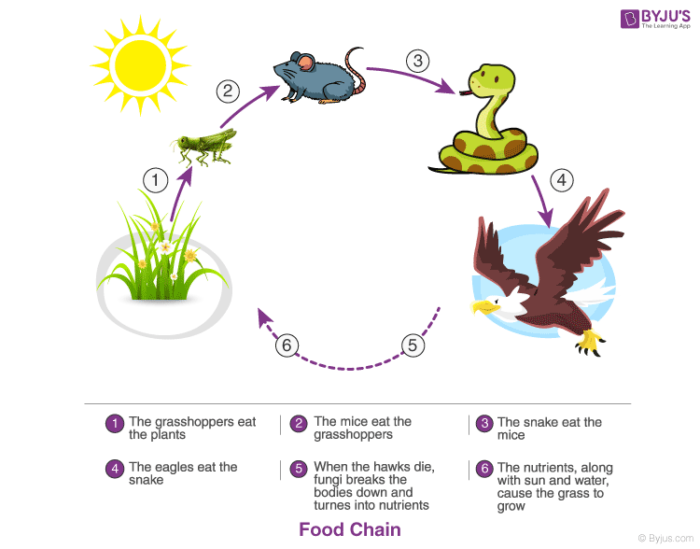

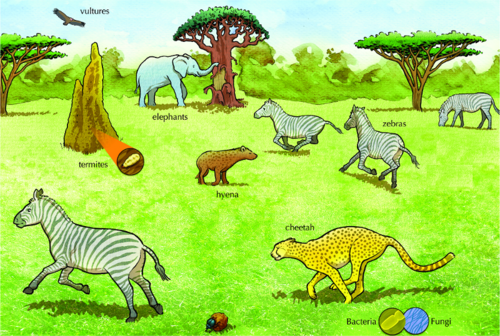

An ecological community comprises multiple species occupying overlapping niches—specific roles involving resource use, habitat preferences, and behavioral patterns.These niches are not static; they evolve in response to environmental pressures and interspecies dynamics. Key functional groups include: - Producers: Photosynthetic organisms like plants, algae, and cyanobacteria that convert solar energy into organic matter, forming the base of energy flow. - Consumers: Herbivores, carnivores, and omnivores that transfer energy through trophic levels, with top predators exerting strong top-down control.

- Decomposers: Fungi and detritivores that recycle nutrients by breaking down dead matter, closing nutrient loops critical to long-term community sustainability. - Engineers and Modifiers: Species such as beavers, earthworms, and corals that physically alter habitats, creating new niches or transforming ecosystem structure. Each group’s contribution reinforces the system’s functional integrity.

For instance, in a temperate forest community, artillery ants not only control insect populations but also indirectly enhance seed dispersal by pruning vegetation, increasing light access for understory plants. This interplay exemplifies how ecological communities operate as integrated systems where species roles are interwoven and mutually influential.

The Adaptive Nature of Ecological Communities

Ecological communities are not fixed entities; they demonstrate remarkable plasticity, adjusting structure and composition in response to disturbances.This resilience hinges on biodiversity: higher species richness buffers communities against collapse, offering functional redundancy and alternative pathways for energy and nutrient flow. Research in grassland ecosystems, such as those in the Konza Prairie Long-Term Ecological Research site, reveals that diverse plant communities maintain productivity even after drought or grazing, whereas simplified systems fail catastrophically. “Ecosystems aren’t just resilient—they’re evolving,” observes Dr.

Raj Patel, ecosystem ecologist at the University of California, Berkeley. “Communities reorganize after stress, but the speed and success of that reorganization depend on how many functional species remain and how tightly they interact.” This adaptability reflects the community’s collective ability to sustain ecological functions, such as carbon sink capacity or water filtration, even amid environmental change. The concept of “community assembly rules” further explains how species come together—whether through dispersal limitation, environmental filtering, or biotic interactions.

These principles reveal that communities emerge not randomly but through predictable processes, shaped by both abiotic conditions and the behavioral preferences of resident species. Human-driven changes, such as land-use conversion or pollution, disrupt these natural assembly rules, often replacing balanced communities with simplified, invasive-dominated assemblages.

Implications for Conservation and Ecosystem Management

Recognizing community ecology’s centrality is pivotal for modern conservation and restoration.Traditional approaches often focus on protecting individual species or isolated habitats, yet safeguarding entire ecological communities demands holistic strategies. Restoring a wetland, for example, requires not only reintroducing key native plants but also reviving the complex network of insects, amphibians, birds, and microbial decomposers that cofunction within that environment. Agroecology exemplifies this paradigm shift: integrating crop-diverse systems, hedgerows, and native pollinators transforms farmland into functional communities that enhance yield stability and reduce chemical inputs.

Similarly, urban planners increasingly incorporate green corridors and native green spaces to foster pollinator communities and improve ecosystem services in cities. Protecting community integrity also means addressing invasive species, which disrupt native interactions by outcompeting local species or preying on keystone members. Effective biosecurity and targeted removal programs depend on understanding community dynamics—not just eliminating threats, but restoring natural balance.

Community in ecology transcends mere species coexistence; it embodies a dynamic web of interdependence, resilience, and adaptation. By defining communities as living systems governed by ecological relationships, scientists and stewards gain critical insight into sustaining Earth’s biodiversity. As climate instability and habitat loss accelerate, understanding and preserving these intricate networks isn’t just an academic pursuit—it is an urgent necessity for planetary health.

Related Post

The Amanda Bynes-Dan Schneider Saga: A Dramedy Legacy Forged in Cultural Fire

Did Vyvan Les Onlyfans Leaks Shake Industry Secrets? Here’s What You Won’t Believe Happened Next.

Word Bomb The Ultimate Word Game: Master the Art of Speed, Skill, and Spelling Excellence