Decoding Water: The H2O Lewis Structure That Explains Life’s Most Common Molecule

Decoding Water: The H2O Lewis Structure That Explains Life’s Most Common Molecule

Molecules shape the world we live in—yet none are as essential or as elegantly simple as water. With its iconic bent shape and precise electron distribution, the H₂O Lewis structure reveals not just chemical detail, but the very basis of biological function. Dominated by oxygen’s electronegativity and hydrogen’s dual role, this molecular blueprint governs water’s unique properties and its irreplaceable role in chemistry, biology, and daily life.

Understanding how electrons arrange in H₂O unlocks a deeper appreciation of why this molecule sustains all known life.

The Atomic Foundation: Oxygen and Hydrogen in Molecular Form

Water’s story begins with two hydrogen atoms bonding to a single oxygen atom—a formation confirmed through spectroscopic analysis and theoretical modeling. Oxygen, the more electronegative partner, pulls the shared electron pair closer, generating a bent geometry around the central atom.“This bent structure isn’t accidental,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a physical chemist at MIT. “It’s a direct result of electron pair repulsion, dictated by VSEPR theory—where lone pairs on oxygen push hydrogen atoms farther apart, minimizing energy.” Hydrogen, though simple in electron count, contributes crucially: two valence electrons form two covalent bonds, fulfilling its octet while enabling high polarity.

Water’s structure arises from sp³ hybridization, where oxygen’s atomic orbitals reorganize to accommodate four electron domains—two bonding pairs and two lone pairs. The lone pairs occupy hybrid orbitals with distinct directional preferences, dictating the 104.5-degree bond angle observed experimentally—slightly less than the ideal tetrahedral 109.5° due to lone pair repulsion.

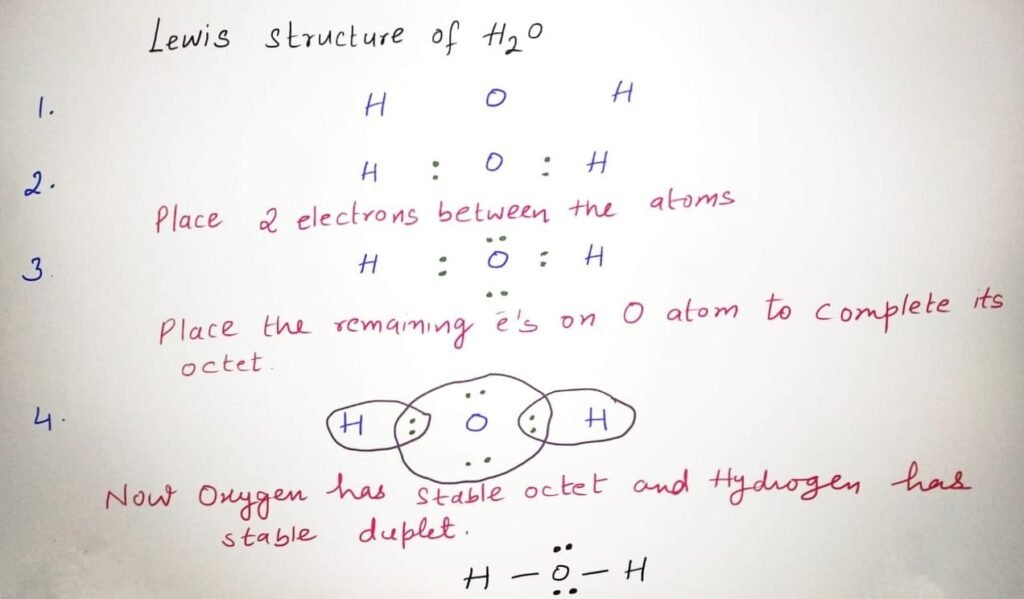

Lewis Structure: Electron Sharing and Bonding Patterns

The Lewis structure for H₂O simplifies complex quantum behavior into a clear visual: two hydrogen atoms covalently bound to oxygen via single bonds, with two lone pairs occupying separate orbitals.Each bond uses a shared pair (2 electrons), whereas lone pairs remain localized—reflecting regions of electron density that resist equal partition. This distribution is not static; rather, it represents an equilibrium where electron motion constantly shifts, stabilized by resonance and promptly polarization effects.

Electron Count and Formal Charges Each bond in H₂O is a single sigma (σ) bond formed by overlap of oxygen’s sp³ hybrid orbital with hydrogen’s s orbital. With shared electrons localized, formal charges remain zero across all atoms—a hallmark of stability.

In contrast, alternative configurations without lone pairs produce higher-energy states prone to collapse. This zero-formal-charge arrangement underscores water’s thermodynamic favorability and synthesis efficiency in nature.

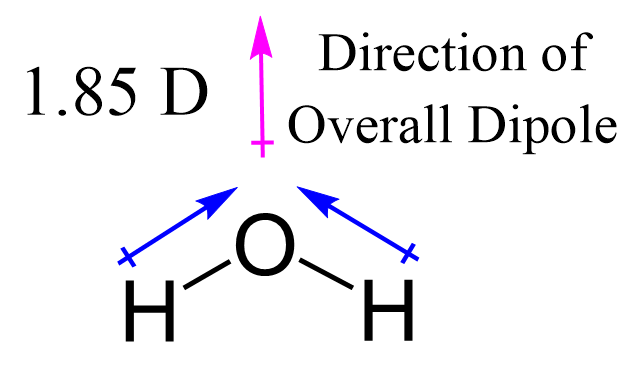

Geometric Influence on Water’s Extraordinary Properties

The bent molecular geometry—Major effect: dipole moment.Unlike carbon dioxide’s linear symmetry, water’s asymmetry amplifies its polarity; the oxygen generates partial negative charge (δ⁻) while hydrogens bear δ⁺ values. This polarity fuels hydrogen bonding—weak but critical interactions stabilizing cell structures, dissolving organic molecules, and maintaining cellular hydration. Hydrogen bonds, explained biochemist Dr.

Marcus Liu, “create a network that elevates water’s boiling point, surface tension, and specific heat—properties unmatched by other common liquids.”

Beyond polarity, the structure dictates water’s high dielectric constant, enabling ion separation in aqueous solutions. This property supports enzymatic function, nutrient transport, and acid-base balance in living organisms. Without this precise proton geometry, biochemical reactions as we understand them would be impossible.

Isotopic Variants and Dynamic Stability

Natural water consists primarily of H₂O, but trace isotopes—especially deuterium (H₂DO) and oxygen-18—introduce subtle shifts in vibrational frequencies and bond strengths. While identical in bonding geometry, these isotopologues exhibit measurable differences in reaction kinetics and phase transitions. Such variations influence evaporation rates, climate dynamics, and isotopic tracing in ecological studies.Looking beyond Earth, water’s Lewis structure remains a universal reference. From interstellar ice grains to alien oceans speculated beneath icy moons, its hydrogen-bonded network emerges as a defining signature of habitability. Understanding its electron architecture is not merely academic—it’s central to astrobiology, climate science, and synthetic life research.

Real-World Implications: From Chemistry to Climate

In laboratories, precise manipulation of H₂O’s electronic structure enables breakthroughs in green chemistry, carbon capture, and drug design. Catalysts utilizing water-inspired motifs exploit hydrogen bonding for efficiency. In environmental science, modeling water’s interactions at the molecular level improves predictive climate models and pollution mitigation strategies.In every drop of rain, glass, or cellular fluid, the H₂O Lewis structure quietly orchestrates reality. Its electron dance—governed by quantum mechanics yet visible through macroscopic phenomena—reveals the hidden order underlying life’s fluid medium. By decoding this structure, scientists not only explain nature but equip humanity to innovate within it.

This intricate blueprint, simple in concept yet profound in consequence, cements water’s status not just as a chemical compound, but as life’s very foundation—written in electrons and bonds.

Related Post

Decoding Ch2O: The Precise Lewis Structure Behind Carbonyl Chemistry

QVC Host Husband Passes from Cancer: A Life of Service Cut Short by Illness