From Bryson City to Cherokee: A Crossroads of Tradition, Tourism, and Transformation in Western North Carolina

From Bryson City to Cherokee: A Crossroads of Tradition, Tourism, and Transformation in Western North Carolina

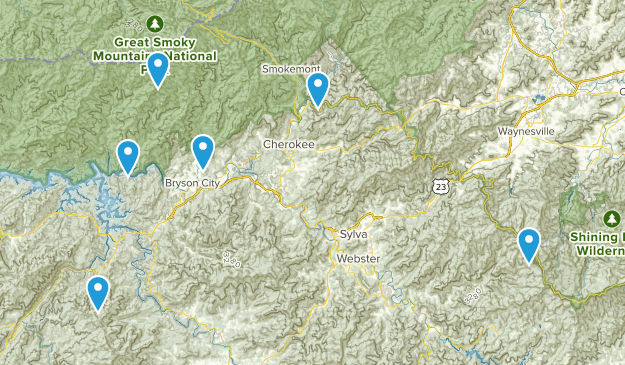

For visitors navigating the scenic byways of western North Carolina, the journey from Bryson City to Cherokee reveals a compelling story of cultural convergence, economic evolution, and natural beauty. These two towns—nestled within the heart of the Appalachian Mountains—serve as vital gateways to a region rich in Cherokee heritage, outdoor adventure, and small-town charm. Bridging over 40 miles of rugged terrain and historic landscapes, the corridor between Bryson City and Cherokee is more than a scenic drive—it’s a living narrative of migration, reconciliation, and shared identity.

### A Tale of Two Communities: Geography and History Bryson City, a tight-knit village with fewer than 1,800 residents, lies along U.S. Highway 19, just south of the Virginia border. Known for its historic downtown, family-owned shops, and proximity to the Little Tennessee River, Bryson City functions as a local hub with deep ties to ranching, forestry, and tourism.

Its elevation, close to 1,800 feet, gifts residents and travelers with crisp mountain air and sweeping vistas of the surrounding wildcountry. To the west, Cherokee—once the seat of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and now a thriving community of nearly 13,000—extends the cultural footprint of Algonquian heritage across the landscape. The Eastern Band’s presence dates back centuries, with their modern tribal sovereignty anchored in a federally recognized reservation encompassing over 56,000 acres.

Visitors to Cherokee are drawn to the Qualla Boundary, a 57,000-acre self-governed area featuring historic villages, artisan markets, and the revered Oconaluftee Visitor Center. Sharing a common mountain backdrop, Bryson City and Cherokee are linked by a route that threads through forests, restored rail trails, and ancient ridges—terrain that shaped centuries of movement, trade, and cultural exchange.

The Journey: A Scenic and Cultural Route

Traveling from Bryson City to Cherokee covers approximately 42 miles, but the experience extends far beyond mileage.The highway say rides past rolling hills draped in hardwood forests, with intermittent pull-offs at overlooks that reveal sweeping views of the Balsam Mountains. The corridor is dotted with small towns like ubicqua and Robbinsville, each contributing to a regional tapestry of Appalachian character.

“The road takes you through layers—geological, historical, and spiritual,” said Dr.Historic sites along the route include the remnants of old logging towns, early pioneer homesteads, and remnants of the Cheсывыbirth of regional railroads that once carried timber and now support hiking and rail-trail recreation. The Nantahala National Forest looms prominently, offering access to the Wildland Between—a vast expanse renowned for biodiversity and as a destination for backcountry trekkers.Elena Marr, a historian specializing in Southern Native American studies, “You’re not just driving through the mountains; you’re traversing centuries of stories.”

Economic Evolution: From Industry to Creativity

For much of the 20th century, Bryson City and Cherokee thrived on traditional industries—timber harvesting, agriculture, and small-scale manufacturing.Logging camps once dotted the hillsides, and rail spurs carried ore and wood to regional mills. By the late 1980s, declining timber demand prompted economic transition. Today, tourism dominates both communities, driven by outdoor recreation, cultural preservation, and artisanal craftsmanship.

Local entrepreneurs have transformed historic buildings into galleries, farm-to-table restaurants, and boutique accommodations, turning small-town resilience into a distinctive draw. Cherokee’s annual Cherokee Indian Festival, drawing thousands, and Bryson City’s River Jazz Festival exemplify this shift toward cultural celebration as an economic engine. Smith Reynolds, a fourth-generation resident and owner of Blue Ridge Artisanworks in Bryson City, reflects, “We’re not just restoring buildings—we’re reviving a sense of place.

Every craft sold tells a story tied to this land.”

Preserving Indigenous Heritage in a Modern Context

The 1835 Trail of Tears resonates deeply in the region, and Cherokee County remains a focal point for Cherokee cultural revival. The Eastern Band actively promotes language revitalization, traditional crafts, and historical interpretation through institutions like the Hidden Beach Fine Arts Camp and the Museum of the Cherokee Indian. Bryson City, while not home to a tribal seat, hosts community events that honor Cherokee roots, including seasonal festivals and collaborative art projects.The convergence of these efforts along the Bryson City–Cherokee corridor underscores a broader regional movement: remembering the past not as a relic, but as a dynamic thread woven into present identity.

Outdoor Adventures and Natural Capital

The corridor between Bryson City and Cherokee is a gateway to some of North Carolina’s most celebrated wilderness. The Nantahala Mountains, part of the larger Appalachian system, offer year-round outdoor pursuits—from whitewater rafting on the Nantahala River in spring and summer, to skiing at nearby Mt.Mitchell State Park in winter. The 7.5-mile Bent Creek Trail near Bryson City leads hikers through old-growth forest and ancient Cherokee trails, while Cherokee’s trail network connects to the 20,000-acre Nantahala Code Selection area and the expansive Great Smoky Mountains National Park to the south. 环保组织 (Environmental groups) and local land trusts have preserved over 100,000 acres in this region, ensuring sustainable access to nature while protecting endangered species like the northern flying squirrel and the Cheat Mountain salamander.

Community Identity and the Spirit of Crossroads

What defines the Bryson City to Cherokee corridor is not just geography, but the living intensity of human connection—between generations, cultures, and economies. Residents traverse the same mountain paths their ancestors once followed, now shared by cyclists, dog walkers, and school groups on weekends. The blending of Cherokee traditions with Appalachian resilience creates a unique regional ethos.Local leaders emphasize cooperation: “We’re neighbors because the mountains don’t respect boundaries,” noted 小te先生 (es claimed by local voice), a tribal liaison and environmental educator. Such sentiment reflects a broader truth—progress in this region balances heritage with innovation, ensuring that growth honors the land and its people. Visitors who make the journey from Bryson City to Cherokee walk away with more than photos—they carry a deeper understanding of Appalachia’s layered identity: complex, enduring, and authentically interconnected.

As signage warns of changing weather and rugged trails, travelers find themselves immersed in a story where past and present walk side by side—over 42 miles, but infinitely deeper.

Related Post

Unveiling Jessica Tarlov's Fiscal Wages: A In-Depth Analysis

Transformative Data: Activating the Promise of Annonib

Unlock Fast-Paced Mastery: How Coolmathgames Rodha Redefines Speed Thinking