How Oceanic Crust Melts Into Continents: The Geological Dance of Converging Plate Boundaries

How Oceanic Crust Melts Into Continents: The Geological Dance of Converging Plate Boundaries

Beneath the surface of Earth’s dynamic crust lies one of the planet’s most profound geological transformations: the convergence of oceanic lithosphere with continental plates. This process, often described as the subduction of dense oceanic plates beneath lighter continental margins, forges mountains, fuels volcanic arcs, and shapes continental growth over millions of years. Far more than a simple collision, the convergence of oceanic to continental crust is a complex, multi-phase sequence governed by heat, pressure, and chemical exchange, driving the evolution of continents and the distribution of natural resources.

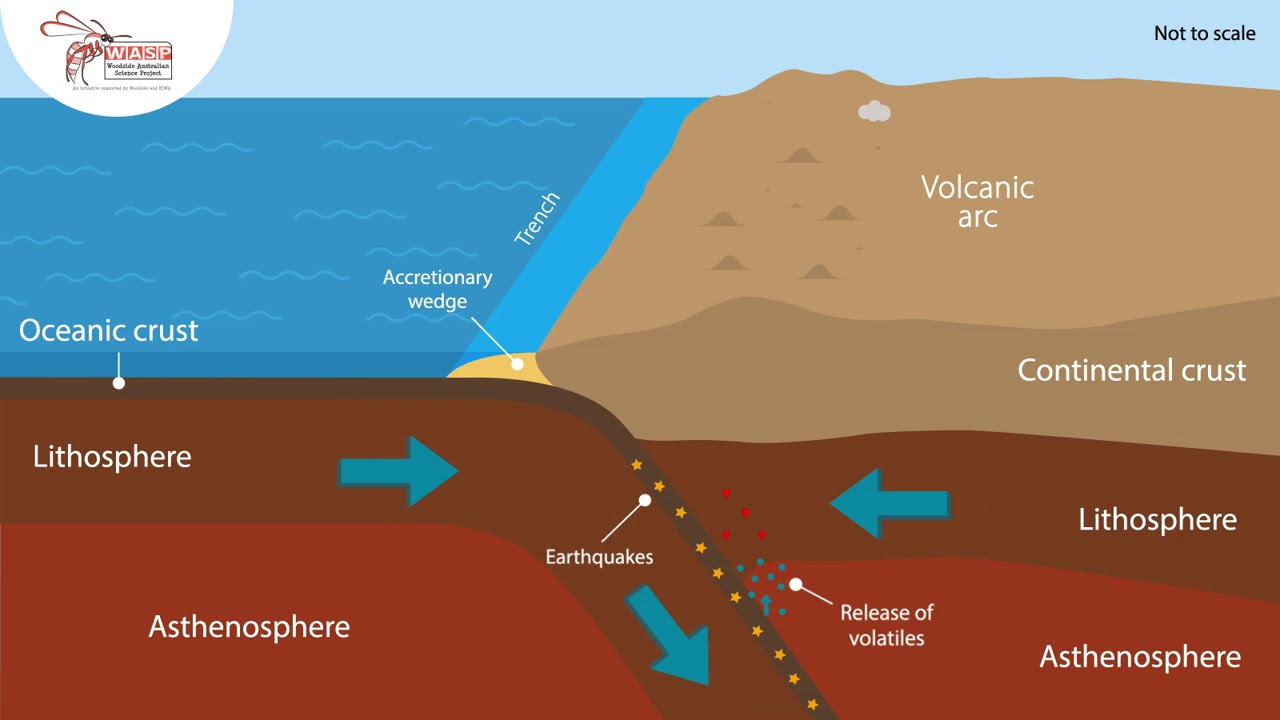

At the heart of this transformation is the physics of subduction zones—regions where the denser oceanic plate, sculpted by eons of seafloor spreading and cooling, plunges into the hot, viscous mantle beneath a continental mass. Unlike the relatively buoyant continental crust, which resists deep burial, the oceanic lithosphere is older, colder, and heavier, making it prone to descent. As it descends, increasing pressure and temperature initiate metamorphic changes and, critically, dehydration reactions.

Sediments and hydrated minerals locked in the subducting slab release water into the overlying mantle wedge—a catalytic step that lowers the melting point of mantle rock, triggering partial melting. This molten material ascends through the continental crust, feeding volcanic arcs and contributing to continental accretion.

The Subduction Cycle: From Ocean Floor to Continental Building

The convergence process follows a precise yet intricate cycle: - **Oceanic Generation:** Seafloor spreads at mid-ocean ridges, forming new, hot, thin oceanic crust rich in basaltic rock. As the plate ages, it cools, thickens, and gains density, eventually becoming a prime candidate for subduction.- **Slab Descent:** Cooling and compaction cause the slab to sink—typically at rates of 3 to 10 centimeters per year—into the mantle. As it descends into the mantle transition zone (between 200 and 700 kilometers deep), it undergoes intense metamorphism, releasing water-rich fluids. - **Mantle Wedge Interaction:** These fluids migrate upward into the overriding continental lithosphere, triggering flash melting in the hot mantle above the subducting slab.

This generates mafic magmas, which migrate upward through fractures and faults. - **Crustal Differentiation:** Magmas interact with the thick, chemically distinct continental crust, undergoing fractional crystallization and assimilation. Over time, these magmas evolve toward more silica-rich compositions, forming granitic intrusions that thicken and stabilize the continental crust.

- **Accretion and Mountain Building:** Repeated subduction events lead to the stacking of volcanic arcs, oceanic terranes, and sedimentary deposits onto the continent, progressively widening and strengthening landmasses. The Andes and the western margin of North America exemplify this long-term accretion, where convergent forces have pile-drived thousands of kilometers of crust into stable continents.

One of the most compelling dimensions of oceanic-to-continental convergence is its role in continental growth.

While continental crust is predominantly ancient, added through episodic magmatism, porphyry intrusions, and accretionary processes, recent isotopic studies reveal that subduction-related magmatism accounts for roughly 60% of new continental crust formation over geological time. This transformation is not merely additive; it alters the composition, thickness, and geochemical signature of continents, enriching them in elements like potassium, uranium, and rare earth metals vital for modern technology.

Historical and geological records document this process across Earth’s history. For example, the formation of the South American continent involved prolonged subduction of the Nazca Plate beneath the continental margin, beginning over 200 million years ago.This sustained convergence built the Andes, generated vast magmatic arcs, and contributed to the evolution of one of Earth’s most biodiverse and mineral-rich regions. Similarly, the accretion of island arcs and oceanic plateaus along the North American west coast—particularly during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic—exemplifies the long-term benefits of oceanic convergence in shaping stable, resource-laden continental platforms.

Yet this powerful geological engine is not without hazards.

Frequent earthquakes, explosive volcanism, and the risk of megathrust tremors underscore the immense energy released during convergence. The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, and the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, stand as stark reminders of the human consequences tied to subduction zone activity.

Nevertheless, understanding convergent oceanic–continental dynamics remains central to both academic research and hazard mitigation, providing vital insights for urban planning, resource exploration, and disaster preparedness.

From the deep-time rhythm of plate tectonics to the immediate threats of seismic activity, the convergence of oceanic and continental lithosphere stands as a cornerstone of Earth’s dynamic systems. It is not just a boundary where plates meet, but a crucible where crust is born, transformed, and preserved. This ongoing transformation continues to shape the planet’s surface, influence its habitability, and direct human engagement with the deep Earth—making the study of convergent boundaries not only a scientific imperative, but a key to understanding the roots of continents themselves.

Related Post

Desene Animate Românești Noi În 2025: A New Era of Romanian Storytelling Starts Now

1988 Horoscope Chinese Deciphered: How the Year Shaped Destiny for the Chinese Zodiac

Streamline CNA Care with Pointclickcare CNA Sign In: Efficiency Meets Accountability

Gainesville Mourns the Passing of Its Beloved Community, Recalling Lives Honored in obituaries