King Charles I: The Monarch Who Helped Shatter a Kingdom

King Charles I: The Monarch Who Helped Shatter a Kingdom

When King Charles I ascended the English throne in 1625, few could have foreseen the seismic political and religious upheaval his reign would trigger—upheavals that culminated in civil war, his trial, and ultimately his execution in 1649. Charles, heir to the Tudor legacy through his father James I, embodied both the divine right of kings and the tensions of an era reshaping British identity. His unwavering belief in royal authority, clashes with Parliament, and ill-fated decisions propelled Britain into a revolutionary conflict—one that redefined monarchy, governance, and religious freedom for centuries.

From the Ulster Plantation to the brutal clash at Edgehill, the reign of Charles I stands as a cautionary tale of absolutism confronted by the forces of constitutionalism. Born on 19 June 1600 at Dunfermline Castle in Scotland, Charles was the second son of James I and Anne of Denmark—himself the last of the Tudor dynasty. Ascending at 24 after his father’s death, Charles inherited a fragile political landscape.

Unlike his pioneer father, who championed royal charisma and centralized power, Charles approached governance with a more introspective and rigid worldview. “The king’s own way is the righteous way,” he wrote, reflecting his belief in divine right—the idea that monarchs ruled by God’s will, not Parliament. This conviction, while central to his identity, would soon alienate key political and social factions across England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Absolute Ambition and the Shattering of Parliamentary Trust

Charles’s reign was marked early by frustration at Parliament’s resistance to his financial and religious policies. Unlike James I, who often relied on adfinance and diplomatic finesse, Charles insisted on raising revenues independently—leading to the controversial use of forced loans and the infamous Ship Money tax, levied even in peacetime. As historian Roy Strong notes, “Charles’s refusal to compromise revealed not just fiscal brinkmanship, but a deep-seated fear that negotiation might weaken royal authority.” Religious discord compounded political tension.Charles, a strong believer in High Anglican ritual and ceremonial uniformity, supported bishops like William Laud, whose push for uniformity alienated Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians. The 1637 introduction of the Book of Common Prayer in Scotland sparked the Bishops’ Wars—armed rebellions that drained the royal treasury and forced Charles to recall Parliament. Yet even this temporarily cooperative session collapsed when Parliament demanded limits on royal power, especially on religious matters.

Charles dissolved Parliament that same year, setting a precedent of rejection that would echo throughout his reign. Key policies and their fallout included: - The Personal Rule (1629–1640): Charles governed without Parliament for over a decade, ruling by prerogative—a period marked by both fiscal strain and religious coercion. - The Powder Load Controversy: His personal involvement in naval preparations “to parade his authority,” as some contemporaries saw it, undermined trust.

- The Bishops’ Wars: Military failure in Scotland forced Charles back to the political stage with an armed necessity he deeply resented. Each maneuver, while aimed at preserving royal dominance, deepened fractures within the nation. By 1640, Charles was trapped: financially bankrupt, militarily vulnerable, and politically isolated.

The Path to War: From Crucial Parliament to Battlefield Conflict

The decade of absence from Parliament did little to quell dissent; it instead radicalized opposition. When Charles summoned Parliament once more in 1640 to raise funds, it was for just four months—known infamously as the Short Parliament, dissolved when MPs refused his financial demands. But before Parliament dissolved, Scottish envoys received promises—later broken—of wider autonomy, only to fuel English Puritan fears of Catholic influence.When Charles finally dissolved this Parliament, it ignited a political firestorm. To survive, Charles dissolved it in August 1640 and convened a new Parliament—The Long Parliament—that would last nearly five years and reshape England. This body rápidamente became the engine of resistance, passing the Triennial Act to ensure regular parliamentary sessions, and initiating legal and political reforms that challenged absolute rule.

For Charles, now increasingly seen as a prisoner of his own principles, this recycling of Parliament signaled not revival—but desperation. As tensions boiled over, religious divides hardened. In Ireland, Charles’s attempts to enforce Anglican practices triggered brutal rebellion—prompting harsh reprisals that inflamed Anglo-Irish animosity.

In England, militant Parliamentarians formed militias, while royalist loyalists fortified key strongholds. The standoff crystallized: one side demanded accountability and shared governance, the other clung to divine right and centralized control. By August 1642, the flashpoint arrived at Manchester and Edgehill, where the first pitched battle of the Civil War shattered the illusion of peace, marking the irreversible descent from constitutional crisis to full-scale rebellion.

His secret marriage to the Catholic Henrietta Maria heightened Protestant fears of enduring absolutism. The failed Scots’ War (1639–1640) cost money, men, and credibility. When conflict exploded in 1642, Charles’s army—though veteran and well-funded—lacked reliable political legitimacy.

Its leadership included figures like Prince Rupert, whose bold cavalry tactics inspired but often outmatched disciplined Parliamentarian units led by Oliver Cromwell. By 1645, the New Model Army’s rise marked a transformation from royalist irregulars to a purely professional force, ensuring Parliament’s ultimate advantage. From Merston to Naseby, the war became not just a struggle for territory but for the soul of governance—centuries-old debates over who held ultimate authority.

Legacy: The Fall of a King and the Birth of a Republic Charles’s surrender in 1646 and subsequent capture by Scottish forces led to a series of flawed negotiations—negotiations that revealed irreconcilable visions: a restored monarchy with constrained power versus a republic rooted in parliamentary sovereignty. His escape from house arrest in 1647 and attempt to ignite royalist uprising embodied both the desperation and the fanatical conviction that defined his final years. Captured again, tried through a regicidal lens unprecedented in English history, Charles was found guilty of “treason against the nation.” On 30 January 1649, he stood at execution in London’s Banqueting House—his silence heavy, his gaze unyielding—as crowd murmured executioner’s words: “God save the King!”—a gesture both ironic and profound.

His beheading marked the end of monarchy as he had known it. For centuries, kings had ruled by divine command; Charles’s rule demonstrated the perils of absolute power unsupported by consent. Though buried simply in a shallow grave at Westminster, his legacy reverberated through constitutional law, parliamentary democracy, and the global struggle for rights.

The Civil War that bore his name did not just change governance—it redefined the relationship between ruler and ruled, a transformation birthed in blood, defeat, and the irreversible march toward modern governance. Even today, historians debate whether Charles saw himself as a divinely protected sovereign or a beleaguered king buckling against inevitable change. But one fact remains indisputable: his reign was the crucible in which the new British state was forged—fiercely contested, irrevocably altered, and eternally watched.

Related Post

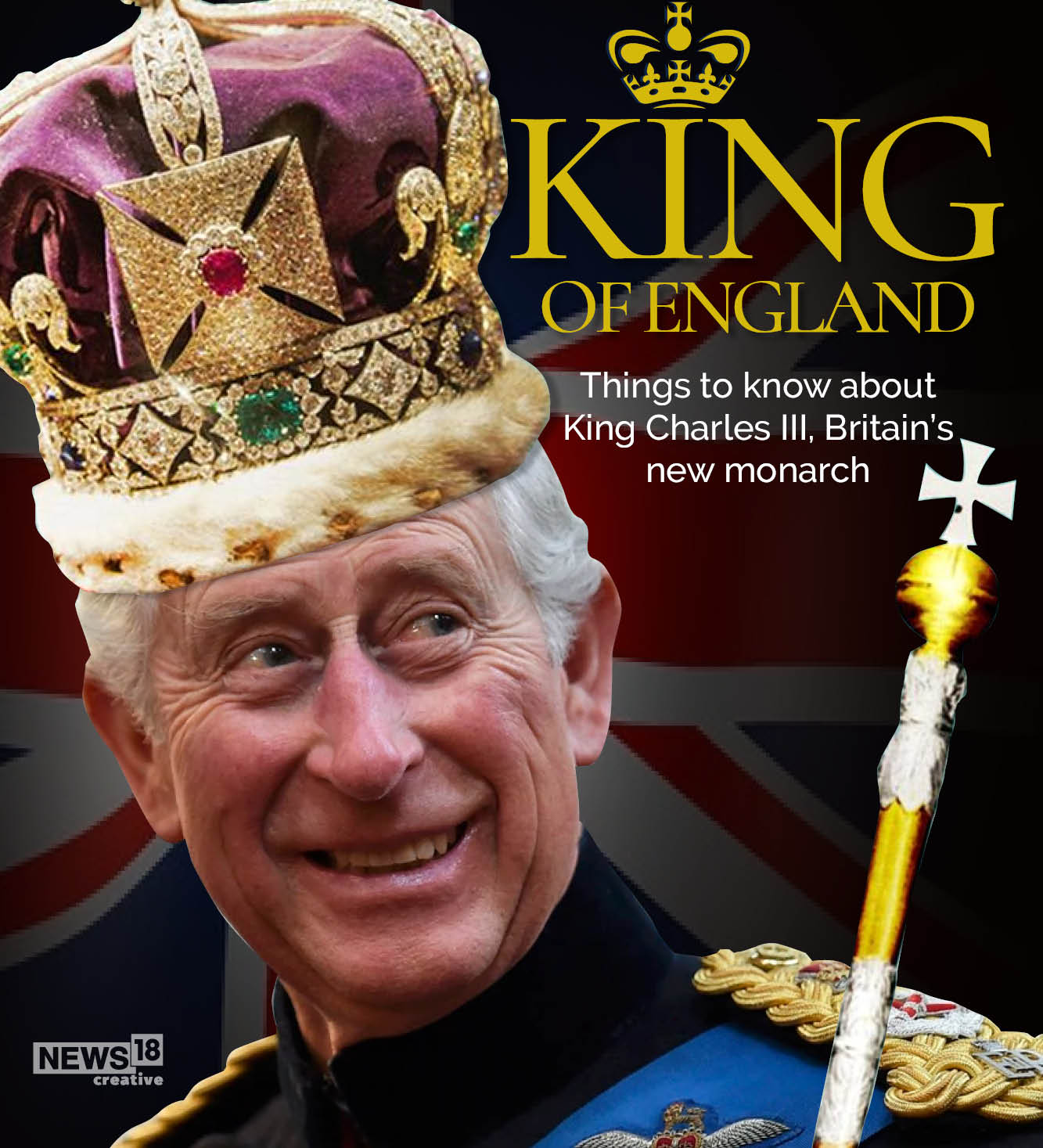

King Charles 111 Emerges as a Steadfast Monarch in Britain’s Modern Age

Injured AEW Star Close To Making InRing Return

Ox vs Cow: The Field Battle of Two Iconic Ruminants and What They Reveal About Livestock, Your Plate, and Our Planet

Larry Fitzgerald: Wife And Kids — A Closer Look at the Family Life Behind the File Photographer