The battle beneath your skin: How keratinized and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium protect the body

The battle beneath your skin: How keratinized and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium protect the body

The human epidermis, the body’s first line of defense against infection, environmental stress, and physical abrasion, is a marvel of biological engineering. Among its most critical components are the stratified squamous epithelia—three distinct tissue layers—each adapted for specific roles: keratinized and nonkeratinized forms. These epithelial types not only reflect evolutionary adaptation but also dictate how the skin functions across diverse body regions.

From the resilient palms to the delicate mucosal linings of the mouth, the strategic deployment of keratinized and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium ensures both protection and flexibility in a constantly challenged environment.

Understanding these epithelial types reveals more than just anatomy—it illuminates the functional arsenal that safeguards human health. Keratinized stratified squamous epithelium (KSE) dominates areas subjected to friction and desiccation, forming a tough, water-resistant barrier.

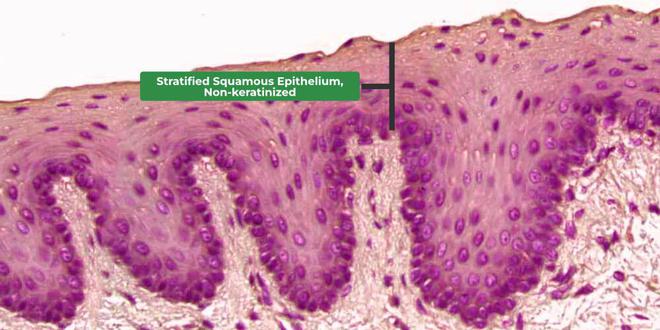

In contrast, nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium (NKSE) lines moist, protected mucosal surfaces where flexibility and moisture retention are paramount. Each type is specialized for its environment, a testament to nature’s precision in tissue design.

Keratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium: Nature’s Tough Shield

The keratinized stratified squamous epithelium is distinguished by its upper layers, rich in keratin—a tough, fibrous protein that strengthens and dries out the surface. This transformation begins in the deeper basal layers, where cells gradually produce keratin and lose their nuclei, eventually forming a dense, protective barrier no longer capable of shedding moisture or repairing itself.This layer, called the stratum corneum, acts as a formidable shield against pathogens, ultraviolet rays, and mechanical wear.

This epithelium thrives in regions subjected to frequent abrasion or water exposure. Most prominent are the palms and soles, where a noncellular, keratin-rich surface prevents infection from cuts and abrasions while minimizing water loss.

Beyond these weight-bearing zones, KSE lines the epidermis of the forearms, legs, and scalp, each adapted to resist daily physical demands. Its structure is defined by progressive cellular maturation and specialized keratin filaments—alpha-keratins—that confer mechanical resilience.

Clinically, the keratinized layer’s impermeability has both benefits and challenges. While it confers exceptional durability, it also impedes repair processes such as wound healing and immune cell trafficking.

Nerve endings embedded within deeper layers monitor for injury, but regeneration is slower due to limited cellular turnover. This trade-off highlights a core principle of biological design: specialization enhances protection but sacrifices regenerative agility.

Nonkeratinized Stratified Squamous Epithelium: The Flexible Guardian of Mucosal Surfaces

Unlike its keratinized counterpart, nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium retains a moist surface layer, thick with mucin and natural moisture retention mechanisms. Found primarily in the oral cavity, esophagus, vagina, and parts of the respiratory tract, NKSE offers a durable yet compliant barrier suited to moist, dynamic environments.Instead of forming a dry, impermeable stratum corneum, NKSE maintains living, hydrated cells with intact nuclei near the base, enabling rapid repair and immune responsiveness.

This epithelium’s cellular architecture supports its key function: flexibility. In the mouth, NKSE lines the inner cheeks and tongue, allowing chewing, speaking, and swallowing without tearing.

Near the vocal cords and within the esophagus, it withstands repeated mechanical stress while preserving moisture to protect underlying tissues from irritation. The absence of heavy keratinization permits constant cellular renewal, a crucial advantage where micro-abrasions occur frequently but healing must remain swift.

The advantages of NKSE extend beyond physical protection. Its vascular-rich superficial layer facilitates efficient nutrient exchange and immune surveillance, enabling quick detection and response to pathogens.

Additionally, the presence of protective mucins forms a slippery, lubricated layer that resists microbial colonization. In clinical contexts, maintaining NKSE integrity is critical—disruptions in mucosal surfaces contribute to infections, inflammatory conditions, and impaired swallowing or breathing.

Comparative Anatomy and Functional Specialization

The distinction between keratinized and nonkeratinized epithelia reflects targeted evolutionary refinement. KSE excels in environments requiring long-term durability and resistance to desiccation, exemplified by skin on the palms and feet.NKSE, in contrast, dominates regions where hydration and flexibility are essential—mucosal linings across the body.

Structurally, both epithelia share common features: a stratified basement membrane, nested layers of squamous cells, and a consistent functional hierarchy. Yet their molecular signatures diverge sharply.

KSE cells express high levels of filaggrin and keratin 10, genes linked to structural rigidity and barrier function. NKSE expresses elevated mucin genes like MUC5B and maintains a denser microvasculature to support hydration and immune cell access. These molecular differences underpin their divergent roles, reinforcing the principle that tissue design follows ecological need.

Clinical and Health Implications

Understanding the functional roles of these epithelial types has direct implications for medicine and dermatology.Keratinization defects—such as those seen in ichthyosis or eczema—compromise barrier integrity, increasing susceptibility to infections and fluid loss. In such conditions, topical treatments aim to restore lipid and keratin balance, strengthening the epidermal shield.

For nonkeratinized tissues, dysfunction often manifests in impaired mucosal healing or chronic irritation.

Yeast overgrowth in dry, cracked mucosa, for example, arises when the protective NKSE barrier fails, allowing pathogens to colonize vulnerable sites. Autoimmune disorders like lichen planus target mucosal epithelium, disrupting NKSE function and leading to painful lesions. Therapeutic strategies increasingly focus on preserving or enhancing epithelial health through probiotics, moisturizers, and targeted immunomodulators.

Takeaways: Balancing Protection and Resilience

Keratinized and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium represent complementary pillars of epidermal defense. KSE provides a durable, moisture-resistant barrier ideal for friction-heavy zones, while NKSE offers flexibility and moisture retention essential for mucosal health. Both epithelia exemplify evolutionary optimization, with cellular architecture and molecular composition finely tuned to their environmental niches.This dual system ensures the skin and mucosal surfaces remain resilient yet responsive—capable of enduring daily challenges while enabling vital physiological functions. As medical science advances, deeper insights into these epithelial types promise improved treatments for barrier-related diseases, reinforcing the irreplaceable role of keratinized and nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium in human health.

Related Post

Chili Or Chilli: How To Spell It Right!

Top 10 Sports Anime You Can’t Miss in 2024: Epic Journeys, Unbreakable Spirit, and Heart-Pounding Competition

La cirugía moderna: Gate divine del cuerpo humano hacia la cura y la transformación

¿Cómo Armar El Cubo De Rubik 3x3? Guía Paso A Paso Para Principiantes