The Hidden Pulse of Soil: Deciphering Its Specific Gravity to Unlock Engineering Secrets

The Hidden Pulse of Soil: Deciphering Its Specific Gravity to Unlock Engineering Secrets

Beneath every footstep, foundation, and construction project lies a silent but powerful determinant of stability—soil’s specific gravity. Though invisible to the naked eye, this key parameter influences load-bearing capacity, settlement behavior, and long-term resilience in geotechnical engineering. Understanding specific gravity of soil is not merely academic; it’s a foundational pillar in ensuring safe, durable, and cost-effective infrastructure across civil engineering applications.

From foundation design to slope stability analysis, specific gravity determines how soil particles interact with water and respond to imposed stresses—making it indispensable for engineers, geotechnical experts, and construction planners.

What Is Specific Gravity of Soil, and Why Does It Matter?

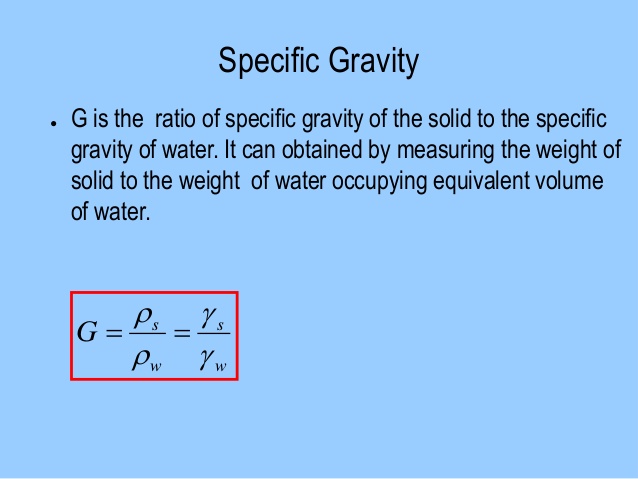

Specific gravity, expressed as the ratio of the density of soil particles to the density of water (typically water at 4°C, with a density of 1000 kg/m³), quantifies how heavy the solid components of soil are relative to water. For most soils, this ratio ranges between 2.6 and 2.8, with denser materials like gravel approaching 3.2–2.6 and clays often falling between 2.7 and 2.9. While total density incorporates moisture content, specific gravity reflects the intrinsic character of mineral inclusions—defaults that set the stage for evaluating particle-to-void relationships in soil mixtures.

This physical property directly influences soil behavior under load.

It determines the void ratio when saturated and serves as a critical input in calculating effective stress, a cornerstone of soil strength assessment. As biomechanical engineer Dr. Elena Marlowe explains, “Specific gravity anchors everything about how soil compacts, how it settling over time, and how it distributes weight.

Without accurate specificity, predictions of settlement or bearing capacity become speculative at best.”

Calculating Specific Gravity: Methods and Medicine

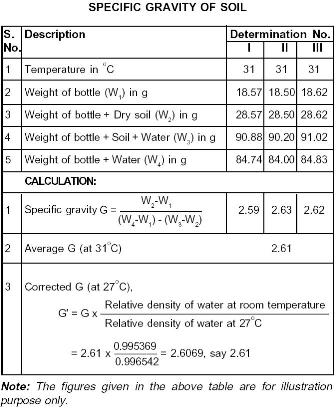

Determining specific gravity demands rigorous laboratory and field techniques, tailored to soil composition and purpose. The standard wet-digestion method remains a gold standard: soil samples are dried, weighed, then fully saturated with deionized water and allowing excess to drain. The weighed wet sample is dried to constant weight, and its dry mass is measured against a known volume of water to compute resulting densities.

Adjusted for saturation, specific gravity is derived using:

- Dry bulk density (mass of dry soil divided by its volume)

- Porosity (1 minus void ratio)

- The saturation ratio (accounting for water filled voids)

For fine-grained soils like clay, the Marshall method or hydrostatic weighing offers greater precision by minimizing air entrapment. In contrast, granular soils such as sand are often assessed via pycnometry, where mercury intrusion porosimetry verifies particle density. Each approach balances accuracy, sample integrity, and field feasibility.

Impact on Soil Classification and Standard Properties

Soil-specific gravity is not a standalone metric—it interacts dynamically with moisture content and soil type to define critical geotechnical parameters.

The void ratio (e), central to soil classification and strength analysis, is inversely tied to specific gravity when total density fluctuates with saturation. For example, a soil with high specific gravity (2.8) and moderate density will rigidly resist compaction at low void ratios, limiting settlement but demanding careful construction sequencing.

Cutting-edge standards such as ASTM D2900 and UCS (Unified Soil Classification System) formalize these relationships, mandating standardized sample preparation and calculation protocols. These guidelines ensure consistency across global engineering projects, reducing interpretation errors that could compromise structural safety.

Role in Foundation Engineering and Stability Design

In foundation engineering, specific gravity dictates how soil distributes loads to the subgrade.

High-specific-gravity soils, predominantly composed of dense minerals like quartz or feldspar, compact tightly, increasing bearing capacity. Engineers rely on this to compute ultimate load-bearing limits, guiding decisions on foundation depth, pile design, or soil improvement techniques like compaction:** “The specific gravity tells us whether a soil will flex under foundation weight or hold firm,” says structural geotechnical specialist Dr. Rajiv Mehta.

“It’s the first clue in predicting movement, settlement, and long-term performance.”

For shallow foundations, particular attention is paid to cohesionless sands and heavy clays, where specific gravity influences shear strength. In slope stability, gradients adjusted for soil density govern failure initiation—steeper slopes on low-specific-gravity cores exhibit different failure patterns than those on dense granular strata.

Practical Applications and Real-World Case Studies

Field applications illustrate specific gravity’s pivotal role. Consider the construction of a high-rise in coastal Mumbai, where abundant silty sands risk liquefaction.

Engineers measured site-specific gravity and found values near 2.65, signaling moderate density and susceptibility to saturation-induced softening. This prompted design modifications: deeper driven piles to stable clay fabrics beneath, plus pre-load compaction to reduce porosity and boost effective stress—preventing catastrophic settlement later.

In agricultural land reclamation, specific gravity helps classify soil texture and compaction potential. A project in Iowa used soil-specific gravity to optimize tillage depth volumes, enhancing root zone aeration and water infiltration.

Similarly, landfill engineering employs these parameters to select optimal fill materials, minimizing long-term leachate migration and

Related Post

Florida Man’s Unprecedented Sept 19 Incident Shocks Nation: What Triggered the Florida Man’s Wild Out?

King Charles I: The Monarch Who Divided a Nation and Shaped Modern Britain