The Molecular Engine of Life: Unraveling the Monomer of Protein

The Molecular Engine of Life: Unraveling the Monomer of Protein

Proteins are the unsung heroes of biology—driving cellular functions, enabling tissue repair, and regulating life’s most fundamental processes. At the core of every protein’s functionality lies the monomer: the single repeating unit, typically an amino acid, that folds and assembles into complex structures. The monomer of protein is not just a building block; it is the foundation upon which biological complexity is constructed, making it indispensable to life at every level, from molecular motors in cells to the architecture of organs.

Understanding the monomer of protein is essential to grasping how biological systems operate. Each amino acid monomer carries a distinctive side chain that dictates chemical interactions, enabling precise folding, binding, and catalytic activity. The diversity among amino acids—over 20 naturally occurring types—undergoes intricate sequential and spatial organization, resulting in proteins with specialized roles.

“The monomer may be simple, but its impact is profound,” notes Dr. Elena Marquez, a structural biologist at the Institute for Molecular Biology. “From enzymatic action to immune response, every protein’s function traces back to this molecular unit.”

Structure and Chemistry of Amino Acid Monomers

An amino acid monomer consists of a central alpha carbon bonded to four distinct groups: an amino group (–NH₂), a carboxyl group (–COOH), a hydrogen atom, and a unique side chain (R group).This configuration forms a tetrahedral chiral center, contributing to the stereochemistry critical for biological specificity. The monomer’s physical properties—such as hydrophobicity, charge, and reactivity—arise directly from the composition of its R group. Types of side chains are categorized as: - Nonpolar: hydrophobic, beneficial for protein cores shielded from water.

- Polar uncharged: form hydrogen bonds, enhancing solubility or transient interactions. - Positively charged (basic): often found in active sites of enzymes or cell-surface receptors. - Negatively charged (acidic) The sequence and chemical nature of monomers determine how a protein folds, influencing secondary structures like alpha helices and beta sheets. As Dr. Marquez explains, “Each monomer chooses its position within the chain, guided by the physical and energetic profile of its side chain—this precision creates functional three-dimensional architecture.” Measuring monomer behavior involves advanced techniques: X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy allow scientists to resolve atomic-level details of protein folding and function. These tools reveal how subtle changes in monomer composition—such as post-translational modifications—can dramatically alter a protein’s capabilities. A single phosphorylation event on serine or threonine, for instance, can switch an inactive enzyme into a rapidly firing catalyst. Protein Synthesis: From mRNA to Functional Monomeric Units

Protein synthesis begins in the nucleus, where genes encode amino acid sequences as messenger RNA (mRNA).

Ribosomes then translate these sequences into individual amino acids delivered by transfer RNA (tRNA). Each amino acid is covalently linked to form a growing polypeptide chain—essentially a linear monomer ribbon—whose sequence defines its future structure and role. However, on its own, this chain lacks biological function.

The monomer must undergo folding supported by chaperone proteins to achieve its native, functional conformation. Without correct folding, proteins aggregate or fail to perform, contributing to diseases like Alzheimer’s, where misfolded amyloid beta builds toxic clumps. Understanding each monomer’s folding pathway has thus become a cornerstone in designing drugs targeting protein misfolding disorders.

The monomer’s journey continues after synthesis: it may serve in signaling cascades, form structural fibers like collagen, power muscle contractions via actin and myosin, or act as enzymes lowering biochemical reaction barriers by thousands of times. “Each monomer is a node in a functional network,” writes Dr. Ray Chen, biochemist at MIT.

“Its properties define not just one action, but a chain of possibilities.”

Functional Diversity Through Monomer Combinatorics

A protein is formed not by a single monomer but by repeating sequences—hundreds or thousands of identical or varying amino acid monomers assembled into structural domains. This modularity allows proteins to evolve sophisticated functions. For example: - Enzymes rely on catalytic monomers within active sites.- Receptors use ligand-binding monomers positioned to trigger cell signaling. - Antimicrobial peptides employ amphipathic monomers to disrupt pathogen membranes. The combinatorial potential of amino acids enables proteins to sense, respond, and adapt.

As research reveals, even minor shifts in monomer composition—such as substitutions in hemoglobin—can alter oxygen transport efficiency, underscoring monomers’ role in fitness and survival across species.

Clinical and Biotechnological Frontiers

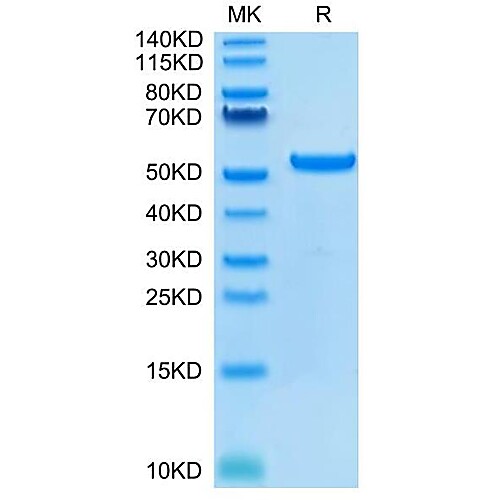

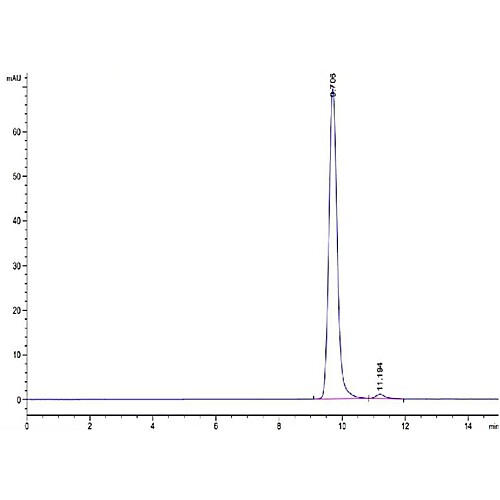

Advances in synthetic biology now allow precise engineering of amino acid monomers. Scientists design monomers with non-natural functionalities—like fluorescent tags or enhanced thermal stability—enabling smart therapeutics.Monoclonal antibodies, built from engineered immunoglobulin monomers, represent a breakthrough in targeted cancer therapy. ewise, monomer-based protein reinforcement is revolutionizing regenerative medicine. Recombinant collagen monomers, for example, mimic native extracellular matrices, accelerating wound healing and tissue repair.

The field continues to evolve, with researchers leveraging monomer specificity to develop biosensors, enzyme catalysts, and bio-inspired materials.

In research laboratories, cryo-EM and artificial intelligence jointly decode monomer dynamics in real time, revealing folding pathways once hidden. These insights promise not only cures for protein-folding diseases but also sustainable biomanufacturing and smart biomaterials.

The monomer of protein—though seemingly simple—remains at the heart of biological innovation.

The Enduring Significance of the Monomer

The monomer of protein is far more than a chemical unit—it is the architect of cellular function, the catalyst of life, and a model of nature’s elegance in molecular design. From folding into precise shapes to driving complex biological networks, these fundamental building blocks shape every physiological process.As science probes deeper into monomer behavior and interactions, a clear truth emerges: understanding the monomer is key to unlocking biology’s most profound mysteries—and harnessing them for medicine, technology, and beyond.

Related Post

Alx James Age Wiki Net worth Bio Height Boyfriend

Michael Chiarello Food Network Bio Wiki Age Wife Wine Restaurants Recipes Salary and Net Worth

Nikki Catsouras Accident: The Shocking Stories Behind the Infamous Photos That Ignited a National Conversation

Owl Beak Types: The Precision Tools of Nocturnal Hunters