The Molecular Mass of Oxygen: A Fundamental Key to Life and Industry

The Molecular Mass of Oxygen: A Fundamental Key to Life and Industry

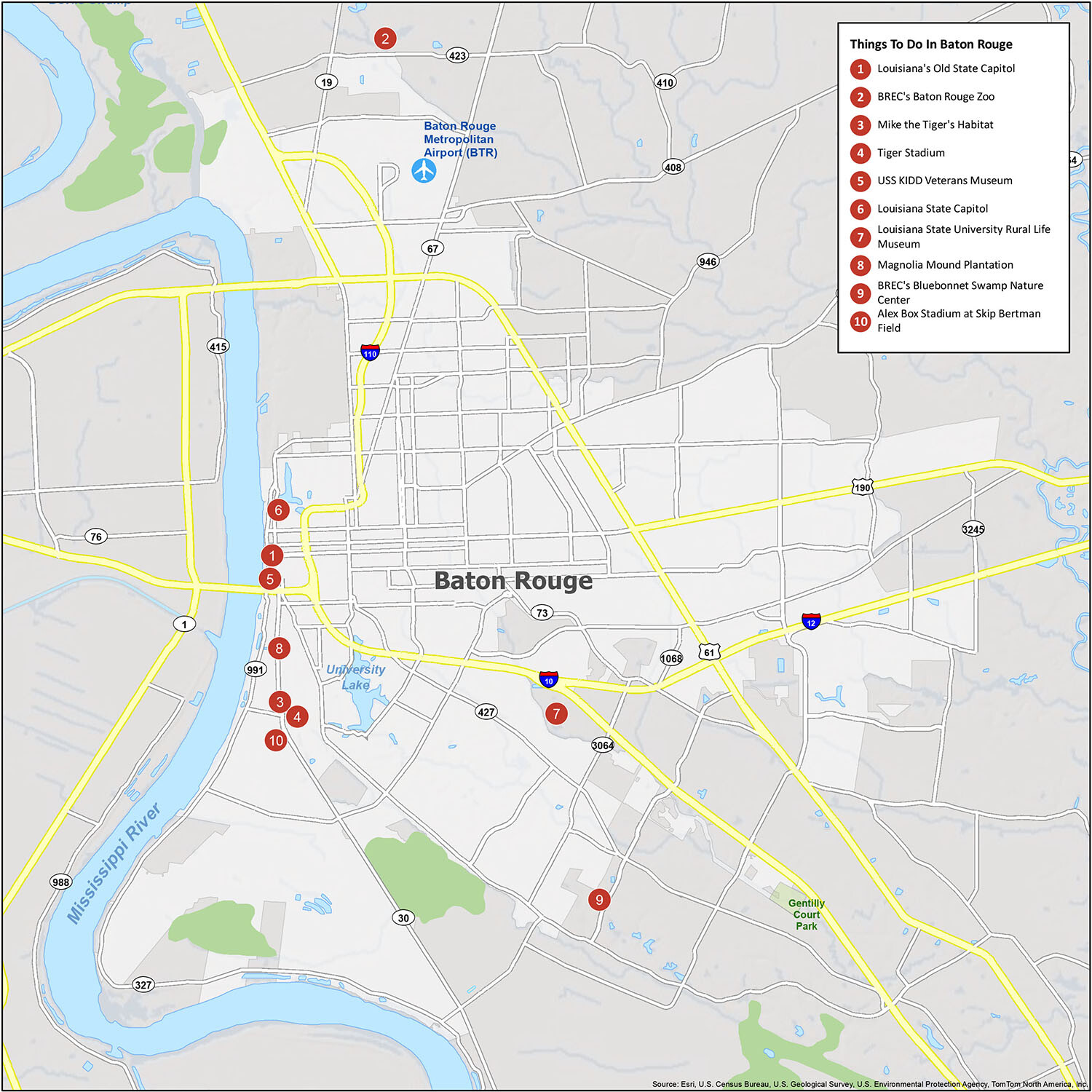

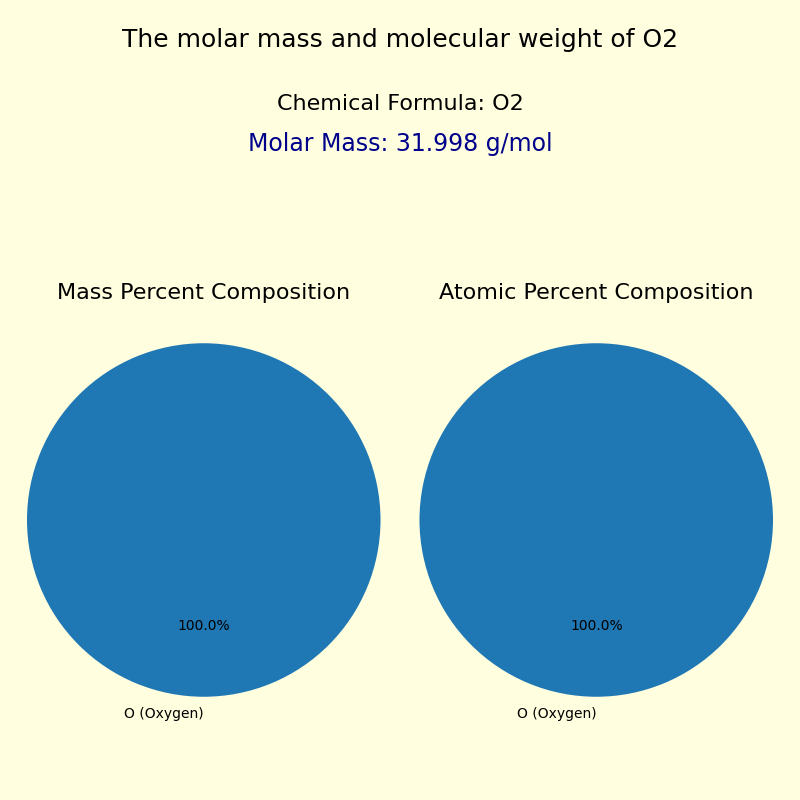

Oxygen, the most abundant element in Earth’s atmosphere, plays a dual role as both a life-sustaining gas and a critical component in countless industrial processes. With a molecular mass of approximately 32.00 atomic mass units (u), oxygen’s fundamental structure—O₂—underpins nearly every breath humans take and fuels technological innovation across sectors. Its ubiquitous presence, chemical reactivity, and precise molecular weight make it a cornerstone of chemistry, biology, environmental science, and engineering.

The Science Behind Oxygen’s Atomic Mass

The molecular mass of oxygen stems from its atomic composition: an oxygen atom consists of 8 protons and 8 neutrons in its most common isotope, oxygen-16 (²⁰¹O), giving it a mass of about 16.00 u, doubled to form O₂ at 32.00 u. This value is not universal—it is weighted by the natural abundance of its isotopes, primarily oxygen-16 (99.76%), with smaller contributions from oxygen-17 and oxygen-18. The standardized atomic weight reflects this isotopic distribution, ensuring consistency in scientific measurement.Oxygen does not exist solo. In the atmosphere, O₂ constitutes roughly 20.95% by volume, making it indispensable for respiration and combustion. Yet, its behavior extends far beyond air: in biological systems, oxygen’s ability to carry one electron enables efficient energy production through cellular respiration.

In chemistry, its strong diatomic bond allows participation in vital redox reactions, while in industry, controlled oxygen flow powers processes from steelmaking to rocket propulsion.

Isotopes and Variability in Molecular Mass

While O₂’s average molecular mass is anchored at 32.00 u, real-world samples reflect natural isotopic variation. Oxygen-16 dominates, but oxygen-17 and oxygen-18—trace isotopes formed through cosmic and geological processes—influence precise measurements.These isotopes affect oxygen’s spectroscopic signature and are critical in paleoclimatology, where fossilized shells or ice core samples reveal past temperatures through isotopic ratio analysis. In laboratory and industrial settings, exact molecular mass determines calibration and safety. For example, oxygen concentrators used in medical care rely on precise molar ratios to deliver oxygen therapy, while in controlled environments like spacecraft or submarines, deviations from standard mass impact efficiency and stability.

Oxygen’s Role Across Diverse Applications

In biological systems, oxygen is the terminal electron acceptor in the electron transport chain, a process producing up to 36 ATP per glucose molecule. Without oxygen’s 32.00 u precision, energy production in mammals would collapse, leading to rapid cellular failure. Oxygen therapy, guided by its molecular weight, supports recovery in patients with respiratory distress or trauma.Industrially, oxygen’s molecular mass defines reaction stoichiometry. In oxy-fuel combustion, excess oxygen reduces waste and boosts efficiency, cutting carbon emissions. In metallurgy, high-purity oxygen stream increases the temperature of blast furnaces, enabling metal extraction from ores with precision calibrated to oxygen’s 32.00 u.

Even in environmental science, oxygen levels in water bodies signal ecosystem health—low oxygen (hypoxia) triggers dead zones, detectable

Related Post

Kikoo Sushi’s Guide to All-You-Can-Eat Sushi: How to Get Maximum Flavor for Every Yen

Tara Wheeler WAVYTV Bio Wiki Age Height Husband Salary and Net Worth

Dipsy Cheese Yankee Recipe Gone Wrong: What Went Awry in This Kitchenzilla Moment

Travel from NYC to DC by Train: Your Smart, Stress-Free Guide to a Smooth Ride