Trigonal Pyramidal Geometry: The Hidden Architecture Behind Molecular Precision

Trigonal Pyramidal Geometry: The Hidden Architecture Behind Molecular Precision

Molecular structures are not random—they follow precise geometric blueprints that determine chemical behavior, reactivity, and function. Among these, trigonal pyramidal geometry stands out as a fundamental configuration with profound implications in chemistry and biology. Defined by a central atom bonded to three peripheral atoms and a lone pair of electrons, this geometry shapes the spatial dynamics of molecules ranging from ammonia (NH₃) to complex biomolecules.

Understanding trigonal pyramidal geometry reveals how electron distribution governs molecular shape, influencing everything from hydrogen bonding to spatial enzyme interactions. This archetypal form exemplifies nature’s elegance in atomic design, where geometry is not just a shape but a driver of function.

The Core Principles of Trigonal Pyramidal Geometry

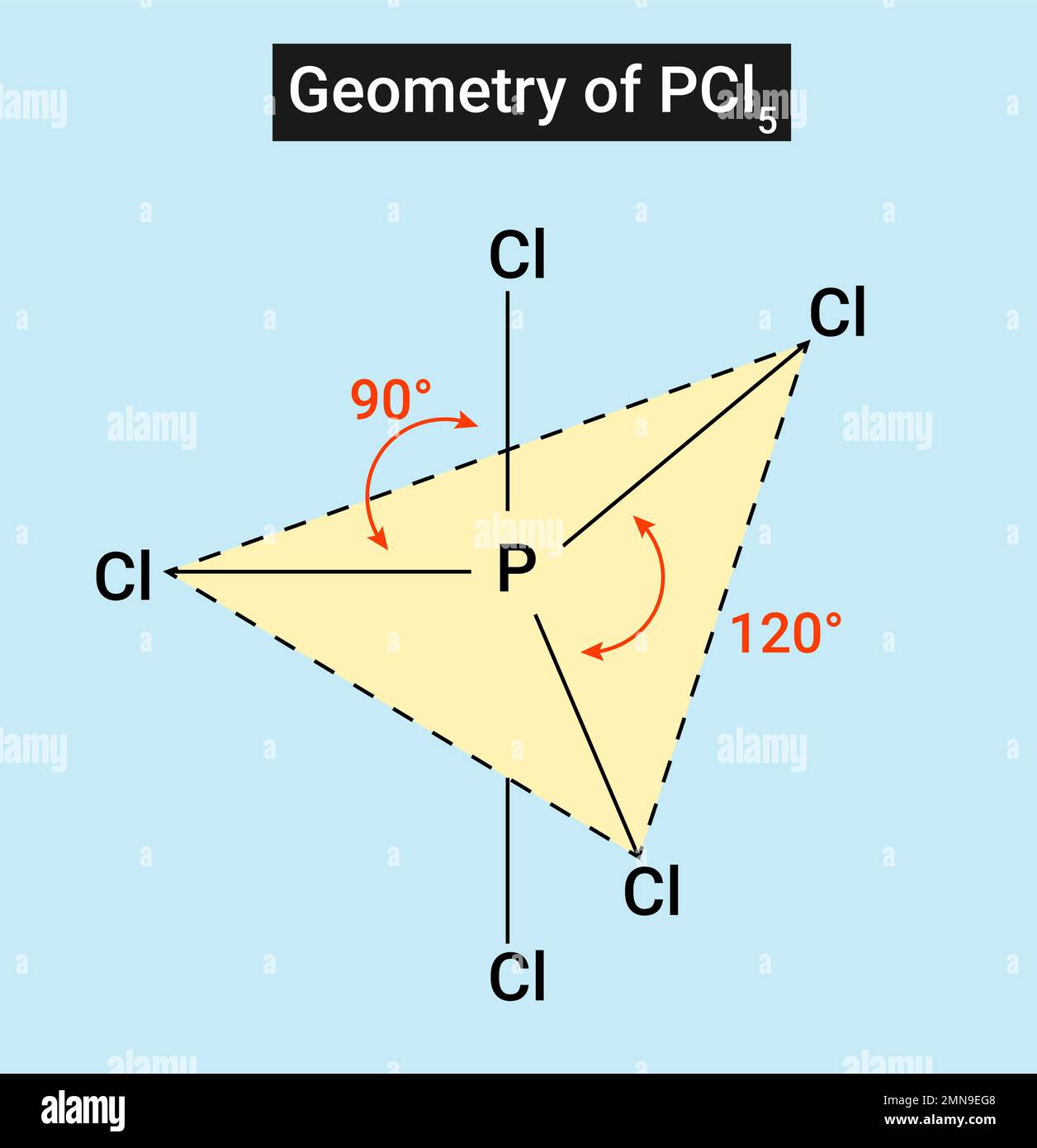

Trigonal pyramidal geometry arises from the interaction between a central atom and three bonding pairs of electrons, accompanied by one lone pair occupying an equatorial position in a tetrahedral electron arrangement.According to VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) theory, electron pairs repel each other, settling into a three-dimensional configuration that minimizes repulsion. The lone pair exerts stronger repulsion than bonding pairs, compressing bond angles between the surrounding atoms. In ideal tetrahedral electron pairs, the angle between bonds is approximately 109.5°; however, the lone pair forces the bonded atoms closer together, typically reducing the H—N—H angle in ammonia from 109.5° to about 107°.

This subtle distortion directly reflects the governing influence of lone pair repulsion, which reshapes molecular symmetry and impacts physical and chemical properties.

The central atom in trigonal pyramidal molecules, such as nitrogen in ammonia, carbon in certain nitriles, or phosphorus in phosphine, serves as the geometric anchor. Its electron domain geometry is tetrahedral, but due to lone pair dominance, the molecular shape deviates into a pyramid.

This configuration creates a distinct region of high electron density above the molecular plane, influencing polarity and reactivity. The asymmetry introduced by the lone pair enables selective interactions—much like how molecular architecture in enzymes directs substrate specificity.

Molecular Examples and Electronic Configuration

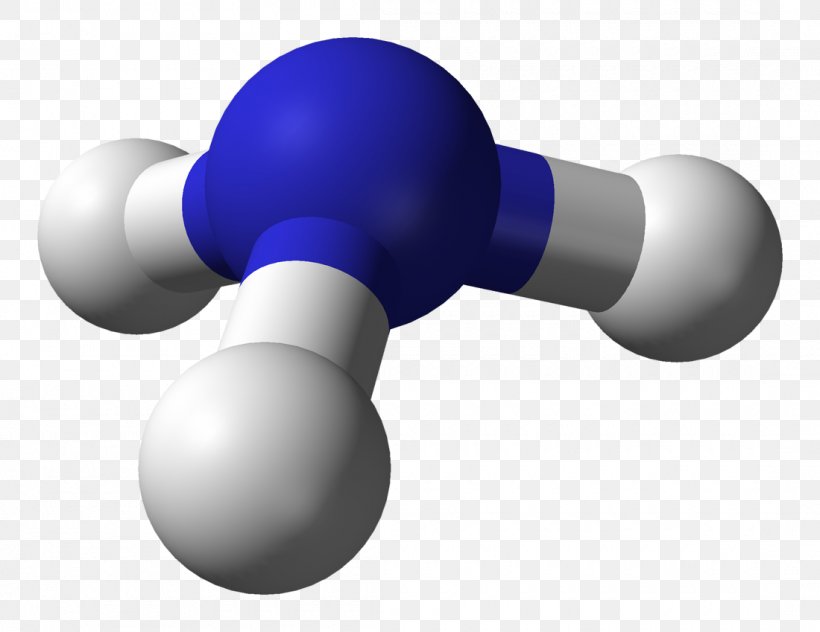

Ammonia (NH₃) serves as the canonical example of trigonal pyramidal geometry.With nitrogen as the central atom, three hydrogen atoms form equatorial bonds while a lone pair occupies the axial position. Nitrogen’s electron configuration (2s² 2p³) includes one lone pair in the sp³ hybrid orbital and three bonding pairs. This hybridization results in directional bonding and a net bond angle of approximately 107°—a measurable deviation from ideal tetrahedral symmetry, evidencing lone pair compression.

Formally, the hybridization leads to four electron domains, with the lone pair occupying one orbital and three forming bonds. The resulting molecular orbitals exhibit asymmetric electron density, generating a permanent dipole moment that enhances solubility in polar solvents and promotes hydrogen bonding. Similar geometries appear in molecules like methylamine (CH₃NH₂), where nitrogen maintains the same electronic arrangement, preserving the pyramidal form.

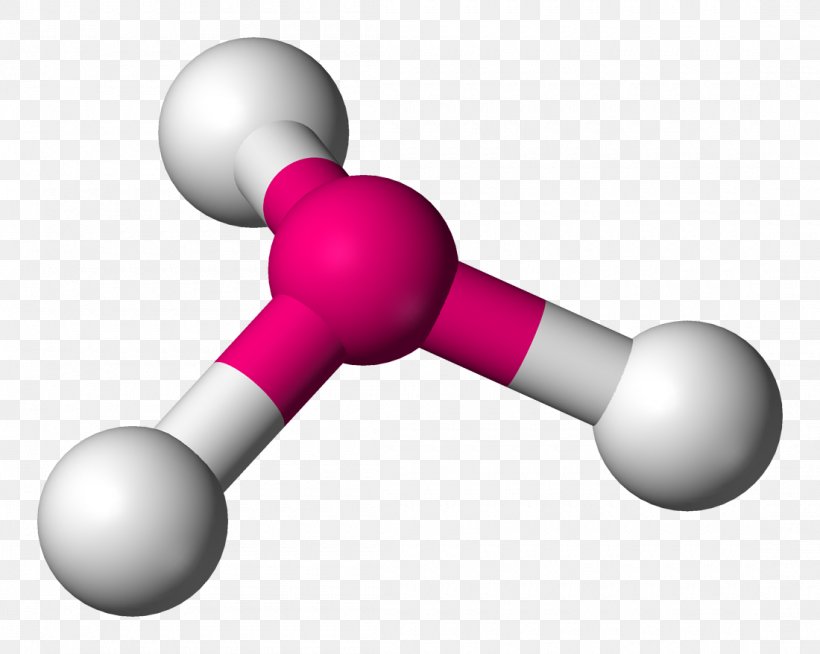

Phosphine (PH₃) follows this pattern with phosphorus as the central atom. Though less reactive than ammonia due to phosphorus’s lower electronegativity and larger size, PH₃ retains trigonal pyramidal geometry. The bond angle, slightly narrower than NH₃’s (~93.5°), reflects phosphorus’s increased atomic radius reducing lone pair repulsion efficacy.

This illustrates how atomic properties modulate geometric parameters even within same structural families.

Implications in Biochemistry and Molecular Function

The trifurcated apex of trigonal pyramidal molecules profoundly affects biological function. In ammonia, the lone pair on nitrogen enables strong hydrogen bonding—a cornerstone of water’s unique properties and crucial in protein folding and nucleic acid structure.Ammonia’s basic character, stemming from NH₃’s lone pair availability, makes it a potent nucleophile and base in biochemical pathways. In carbon-based chemistry, though carbon rarely forms trigonal pyramidal molecules under standard conditions, diamond-like polystructures or strained systems under specific pressures or catalysis can exhibit pyramidal coordination, altering electronic and mechanical behavior. More commonly, nitrogen analogs such as amines leverage this geometry for designing catalysts, drugs, and functional materials.

The lone pair’s reactivity is harnessed in enzymatic reactions where nitrogen nucleophiles attack electrophilic substrates with precision shaped by spatial orientation. Biomolecules like amino acids and neuroligands often incorporate trigonal pyramidal motifs in side chains or active sites. The geometry influences binding specificity: enzymes rely on geometrically complementary cavities where the lone pair participates in hydrogen bonding, charge neutralization, or coordination with metal ions.

For example, the ammonium-derived guanidinium group in arginase features a pyramidal nitrogen that stabilizes transition states through directional interactions.

Visualizing the Trigonal Pyramid: Symmetry and Spatial Insight

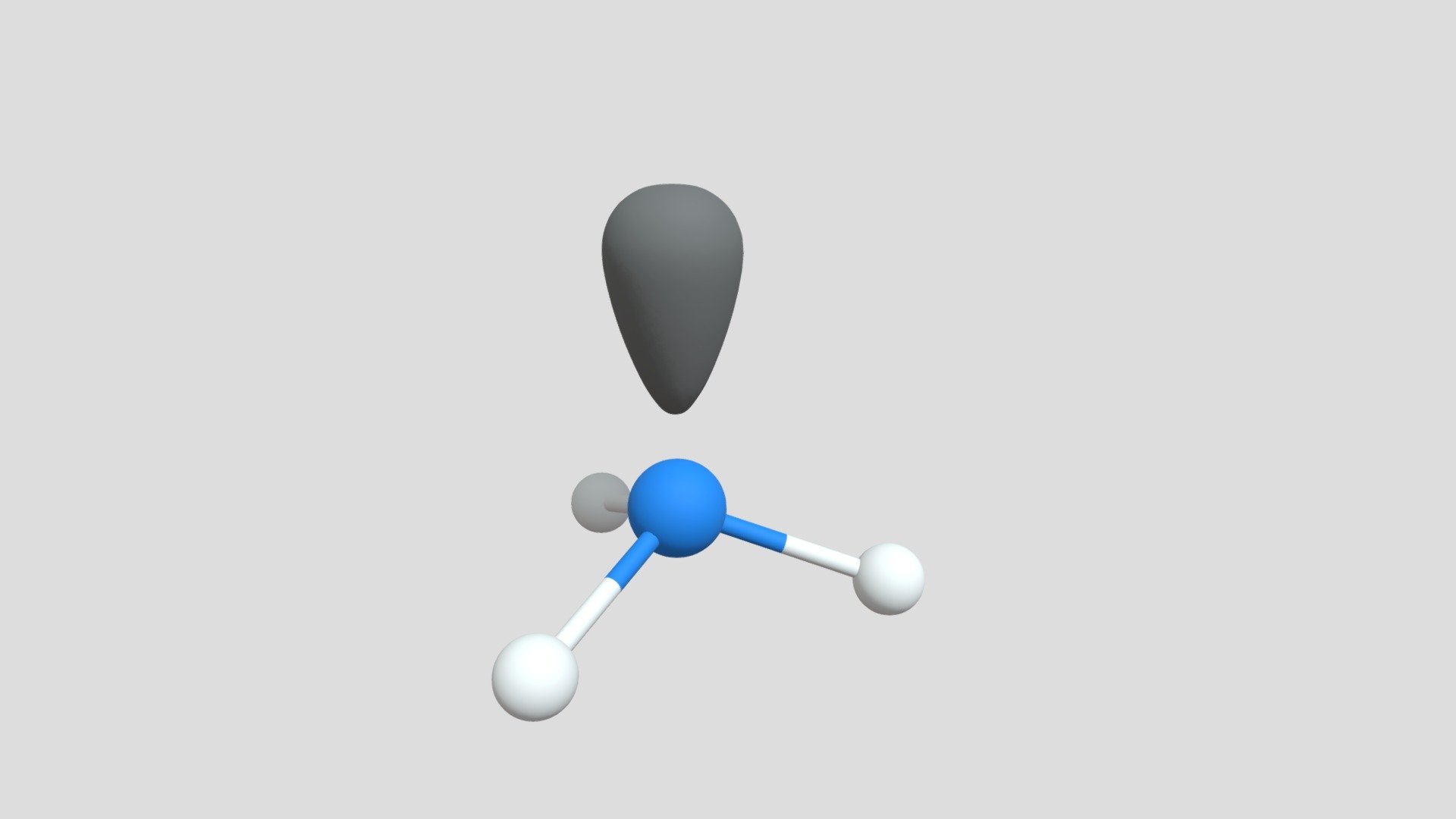

Understanding trigonal pyramidal geometry gains clarity through visual modeling. Molecular diagrams show central atoms surrounded by three bonded atoms and a distinct lone pair positioned above, illustrating the spike-like projection from the plane.This apex-emphasized model reveals how asymmetric electron distribution breaks perfect symmetry. Three-dimensional rendering further highlights bond angle distortion—angles compressed below their ideal tetrahedral values—providing tangible evidence of lone pair dominance. Such visual representations not only aid conceptual grasp but also support predictive modeling in computational chemistry.

Researchers use these depictions to simulate reaction mechanisms, analyze steric hindrance, and design targeted molecular interactions.

In technology, 3D molecular visualization tools increasingly integrate trigonal pyramidal configurations to predict molecular behavior in drug design, nanomaterials, and environmental chemistry. By mapping electron repulsion geometrically, scientists anticipate properties like solubility, reactivity, and binding affinity before synthesis, accelerating innovation across fields.

The trigonal pyramidal geometry exemplifies how subtle electronic effects translate into profound structural and functional consequences.

From simple inorganic compounds to complex biological systems, this archetype underscores nature’s precision and the critical role of spatial design in molecular science. Recognizing and applying its principles continues to advance research, compelling a deeper appreciation for the invisible architecture governing chemical reality.

In sum, trigonal pyramidal geometry is far more than a classroom concept—it is a silent architect of molecular identity, shaping reactivity, polarity, and biological functionality with mathematical grace.

Related Post

Unlocking Verified Credentials: The Essential Guide to Nys Security License Lookup Procedures

HowOldIs Stephen King? Unraveling the Age Behind the Gothic Masterpiece

Roy Van Nistelrooy: The Goal Machine Who Turned Efficiency Into an Art

Corvette ZR1 2025: Price, Specs, and What buyers Must Know Before Bridging the Throttle