Unlocking Chemical Bonds: How Lewis Dot Structures S Reveal the Language of Molecules

Unlocking Chemical Bonds: How Lewis Dot Structures S Reveal the Language of Molecules

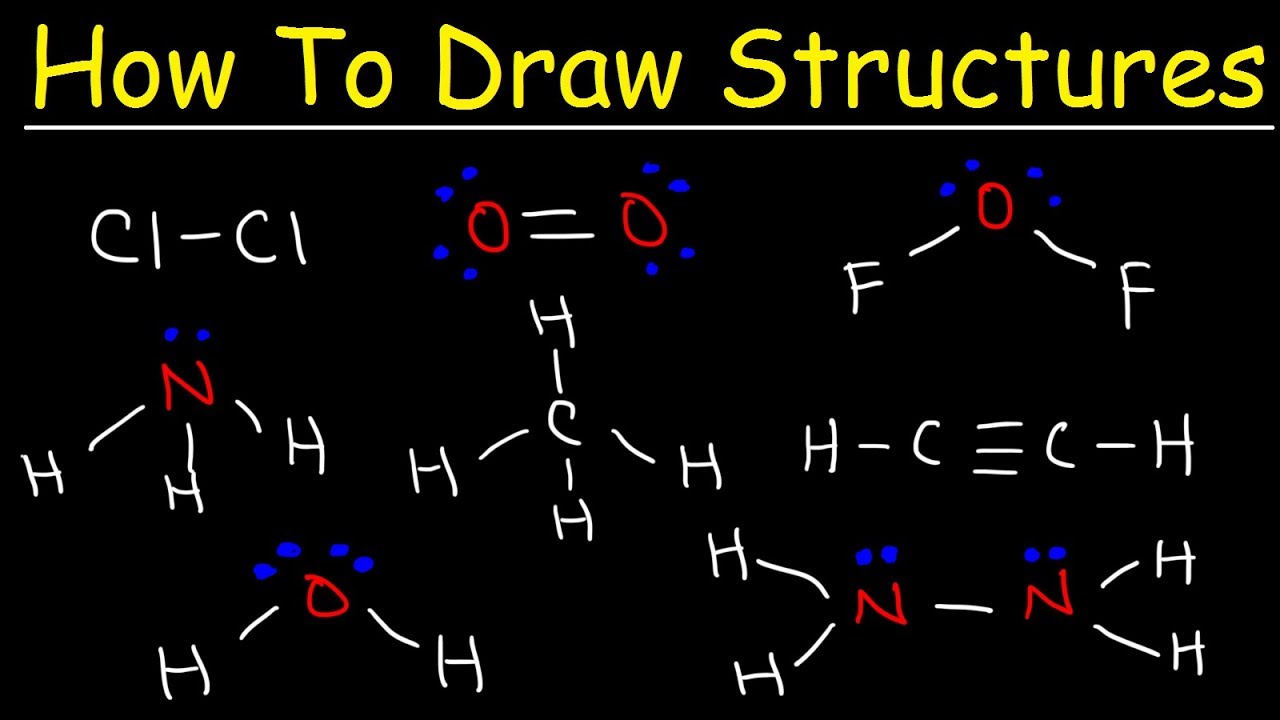

At the heart of chemistry lies a silent yet profound visual language—the Lewis dot structure S—where dots and lines tell the story of how atoms bond and interact. More than mere sketches, these representations decode the invisible forces shaping molecules, from simple diatomic gases to complex biomolecules. By mapping electron distribution with precision, Lewis dot structures reveal the rules governing molecular stability, reactivity, and geometry, forming the foundation of modern chemical understanding.

Decoding the Lewis Dot Structure S: The Visual Grammar of Bonding

Lewis dot structures S are the cornerstone of chemical representation, using dots to denote valence electrons and lines to depict covalent bonds between atoms.

Originally introduced by Gilbert N. Lewis in 1916, this system transformed abstract electron behavior into a tangible diagram. Each dot signifies a single electron, while line pairs represent shared electron pairs forming stable bonds.

The structure’s power lies in its simplicity: it distills complex quantum mechanics into a clear, accessible format, enabling chemists to predict molecular behavior with remarkable accuracy.

Alexander Francis Butlerov and Gilbert Lewis independently pioneered early bonding theories, but Lewis refined the method by emphasizing electron valence—arguing that only valence electrons participate in bonding. This insight underpins modern structures S, where atoms are positioned to minimize charge and maximize pairing. For example, a Lewis diagram for water (H₂O) shows oxygen center with two lone pairs and two bonds, visually interpreting its bent geometry and polar character.

These visual records are not artistic approximations but precise scientific tools, guiding everything from phase prediction to reactivity analysis.

The Builders of Stability: Valence Electrons and Bond Formation

Central to Lewis dot structures S is the meticulous accounting of valence electrons—the outermost electrons available for bonding. Atoms arrange themselves in diagrams to achieve an octet (or duet for hydrogen), minimizing energy through shared, transferred, or lone pairs. Oxygen, with six valence electrons, typically forms two bonds to complete its octet, while carbon, with four, shares four electrons via covalent links.

This electron-counting logic dictates the shape and strength of molecules: ammonia (NH₃) with nitrogen forming three bonds and one lone pair exhibits a trigonal pyramidal structure, drastically altering its chemical behavior compared to methane (CH₄), where full octet filling yields a perfect tetrahedron.

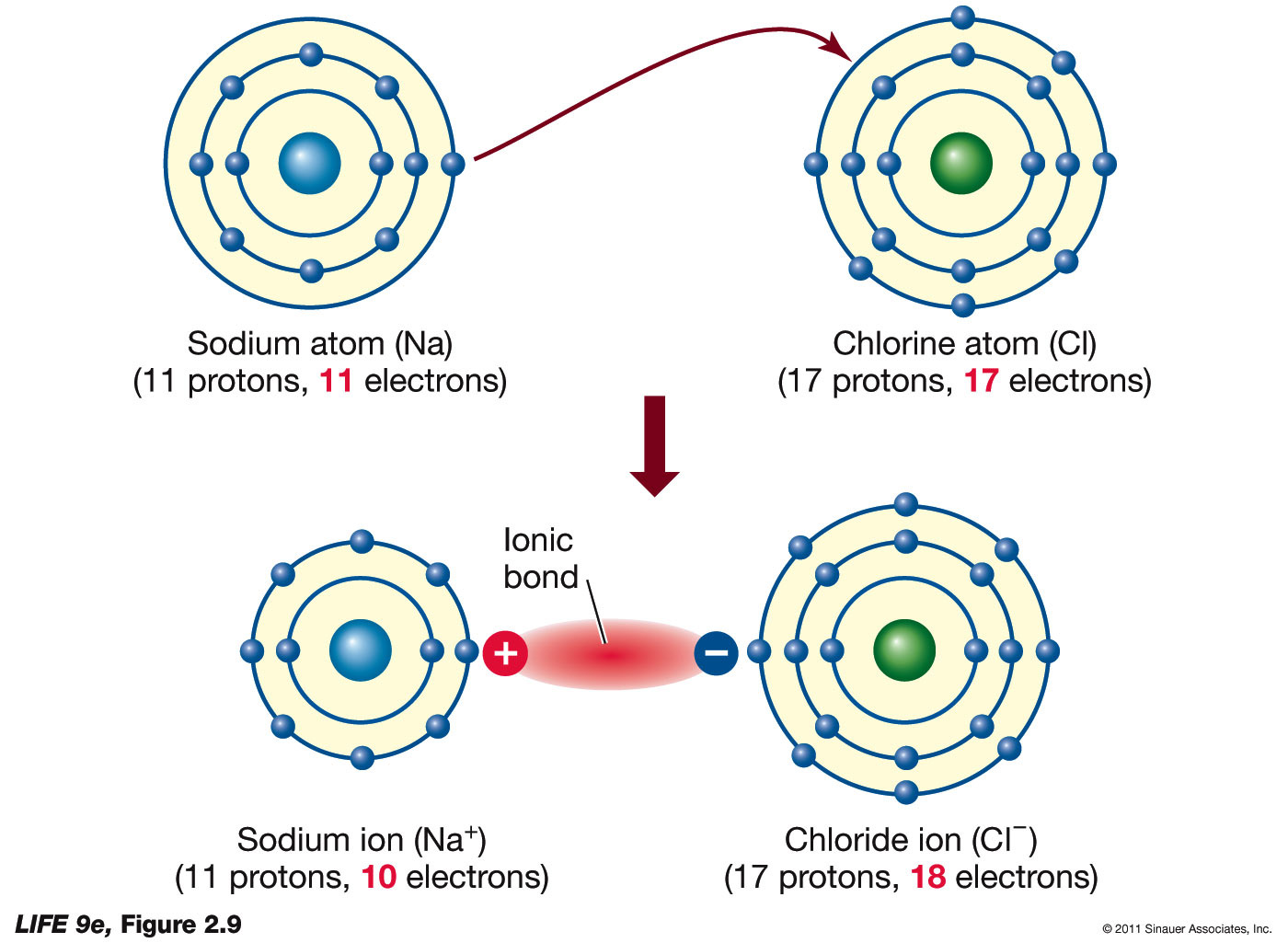

Bonding types emerge clearly in these diagrams: single, double, and triple lines distinguish single (shared pair), double (shared two), and triple (shared three) connections. They also reveal ionic tendencies through stark electron transfers—such as sodium chloride (NaCl), where sodium donates an electron to chlorine—contrasting shared covalent bonding. Objectivity in Lewis structures S enables facile comparisons: a molecule with partial charges (like CO₂) becomes visually legible through polaried dot patterns, exposing electrostatic forces that drive solubility, melting points, and intermolecular interactions.

Molecular Geometry and Reactivity: The Hidden Forces Revealed

Beyond electron count, Lewis dot structures S lay the groundwork for predicting molecular geometry via VSEPR (Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion) theory.

By identifying bonding pairs and lone spaces, chemists map electron domain arrangements—linear, trigonal planar, tetrahedral—directly influencing molecular shape. Carbon dioxide (CO₂), for instance, exhibits linear geometry from two double bonds occupying opposing positions, resulting in symmetry and minimal dipole moments. In contrast, water’s bent form arises from two bonds and two lone pairs compressing the H–O–H angle to 104.5°, a deviation that enhances polarity and drives hydrogen bonding.

This geometric insight directly correlates with reactivity.

Molecules with exposed reactive sites—such as carbonyl carbons in aldehydes or ketones—display pronounced electrophilicity, attracting nucleophiles. Similarly, O–H bonds in alcohols show lone pairs available for proton transfer, explaining their weak acidity. Lewis diagrams map these susceptibilities: phenol’s resonance-stabilized structure includes a lone pair on the oxygen, increasing acidity compared to non-conjugated alcohols.

“Lewis diagrams reveal the architecture of vulnerability,” notes synthetic chemist organic chemist Sarah Chen, “showing where bonds form—and where they might break.”

Notable applications span disciplines: in enzyme catalysis, Lewis structures clarify proton sharing in active sites; in materials science, conjugated π-s

Related Post

Dani Beckstrom Wabc Bio: Decoding the Science Behind Age, Weight, and Sustainable Weight Loss

Top Onlyfans Earners 2023: Who Made Over $1 Million? The Unprecedented Wealth Built on Exclusivity

David Muirs Personal Life Revealing The Enigmatic Side Of The Abc News Anchor

Saturn Company Logo Embodies Innovation, Trust, and Timeless Brand Legacy