Unveiling the Inferior Anatomy: The Hidden Architecture Beneath the Surface

Unveiling the Inferior Anatomy: The Hidden Architecture Beneath the Surface

Understanding the human body’s structure is foundational to medicine, surgery, and biomedical research—and nowhere is this more critical than in the realm of inferior anatomy. Defined as the anatomical structures located inferior to a reference point, typically the horizontal plane or pelvic level, inferior anatomy encompasses complex, often underappreciated tissues stretching from the pelvis upward through the lower torso. These includethe bladder, rectum, reproductive organs, pelvic bones, nerves, and vascular networks, all interwoven in precise neural, vascular, and biomechanical relationships that govern function and pathology.

Ignoring or misunderstanding this domain can hinder diagnosis, complicate surgical precision, and influence treatment outcomes profoundly.

At its core, inferior anatomy refers to the anatomical zones positioned below a defined anatomical level—most commonly referenced at the mid-pelvis or lower abdominal plane. This region houses vital hollow organs, supporting musculature, and intricate nerve pathways none of which exist in isolation.

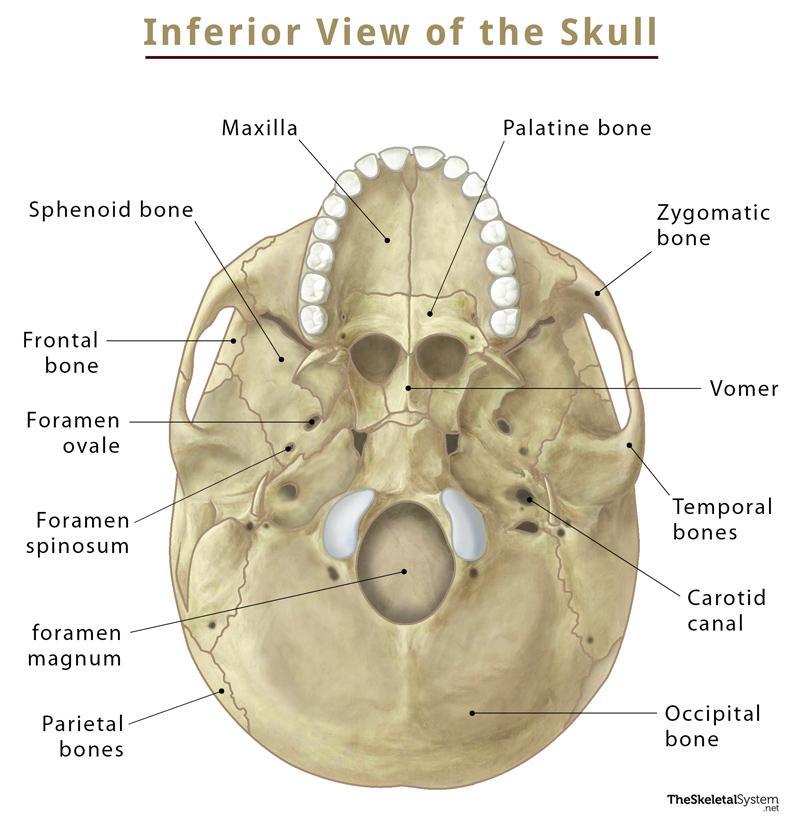

The pelvis, a central focus, consists of the sacrum, coccyx, and paired hip bones (cephalic and divisive sutures), forming a structural basin that bears weight, stabilizes movement, and protects dense neural circuits. The inferior portion of this region includes the distal urogenital components: the bladder, vara portion of the small bowel in select anatomies, and the rectum, a muscular segment essential for fecal storage and evacuation.

The interaction between bony architecture and soft tissue dynamics defines inferior anatomy’s complexity. For example, the sacral hiatus permits lumbar and sacral nerve roots to exit and innervate pelvic organs, creating a neural web critical for sphincter control and sensation.

Meanwhile, the vaulted pelvic cavity cradles the bladder and rectum within a framework of pubococcygeal fascia, supported by the levator ani and puborectalis muscles, whose coordinated function maintains continence and supports abdominal pressure.

Key structures in this domain include:

- Pelvic Bones: The ilium, ischium, and pubis merge at the sacrum, forming a stable base. The sacral canal below supports neural and vascular integrity.

- Bladder andRectum: The bladder transitions inferiorly, its muscular wall adapting to volume changes, while the rectum extends into the sacrococcygeal region—sites frequently implicated in surgical interventions and chronic conditions.

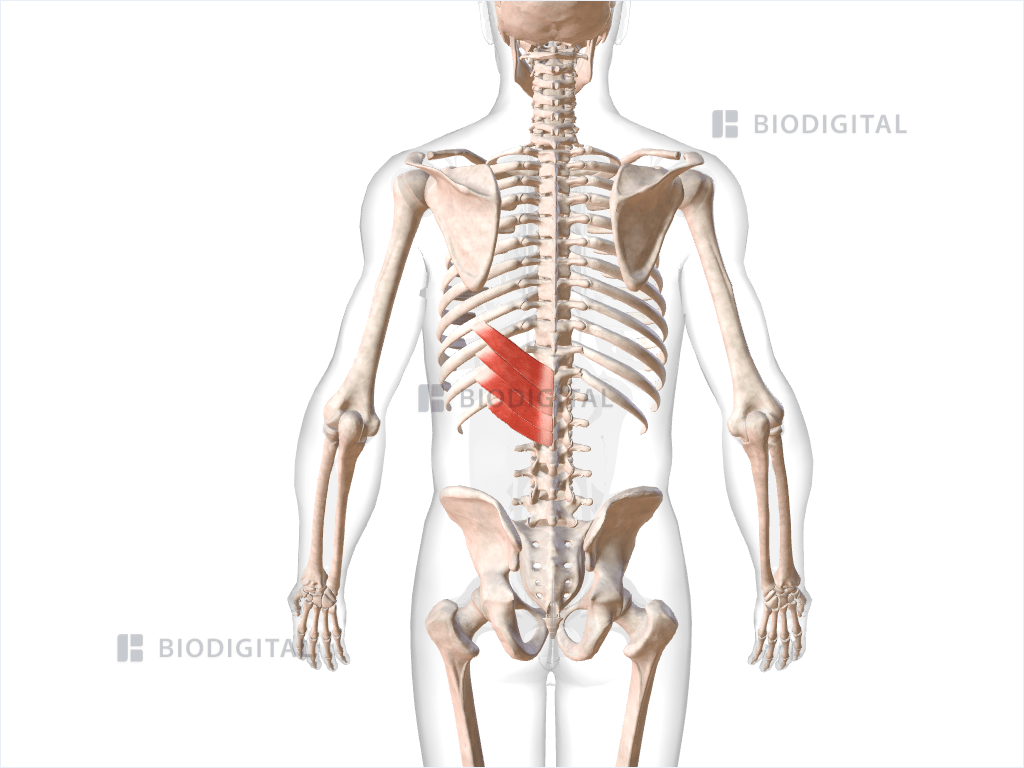

- Pelvic Floor Musculature: Comprising the levator ani complex and coccygeus, these muscles form a dynamic sling preventing organ prolapse, essential for both continence and core stability.

- Nerves and Plexuses: The pudendal and sacral plexuses branch extensively here, carrying sensory and motor signals that regulate bladder function, sexual response, and bowel movements.

- Blood Supply: Epicreal arteries and veins nourish pelvic tissues with dual arterial injections—superior vesical, internal iliac, and middle rectal arteries—forming anastomotic networks that ensure perfusion even during physiological stress.

The clinical significance of inferior anatomy becomes starkly evident in common medical challenges. Pelvic organ prolapse, affecting over 40% of postmenopausal women, arises when supportive ligaments weaken, allowing organs like the bladder or uterus to descend—a direct consequence of compromised inferior structural support.

Similarly, rectal prostate malignancies lie embedded within this region, demanding precise surgical navigation through velvety nerve plexuses and dense vascular fields to minimize complications. Even non-invasive conditions, such as chronic pelvic pain or prostate inflammation, often trace their origins to subtle anatomical distortions or nerve sensitization in the inferior pelvis.

Advances in pelvic MRI and intraoperative imaging are transforming how clinicians visualize and interact with inferior anatomy. These tools enable surgeons to map nerve pathways in real time, preserving erectile function and continence in radical prostatectomies or decompressing neurovascular bundles during sacral decompression.

Meanwhile, research into pelvic floor biomechanics underscores the functional integration of muscles, fascia, and neural feedback—redefining treatment paradigms for incontinence and organ sagging beyond mere surgical repair.

What makes inferior anatomy so pivotal is its role as a bridge between structure and function. Every nerve, vessel, and organ here communicates in a symphony of support, sensation, and propulsion—poorly mapped, this network becomes a silent source of dysfunction. Understanding its nuances is not merely academic; it is essential for healing, preserving quality of life, and pushing the boundaries of medical innovation.

To master the inferior anatomy is to master the hidden engine of vital bodily function, where precision meets physiology in the most intimate architectural zone of the human body.

Neurovascular Foundations: The Inferior Pelvis as a Nexus of Control

Beyond static anatomy, inferior anatomy reveals a dynamic orchestration of neural and vascular systems indispensable to pelvic function. The sacral and lumbar plexuses, rooted in this region, deliver bidirectional signals governing everything from bladder emptying to sexual arousal. These networks are densely innervated by pelvic splanchnic nerves—branches of spinal segments S2–S4—whose precise

Related Post

Unlock Your Digital Potential: Mastering Psn Login for Seamless Access to Powerful Public Services

Meg McNamara Wjz Bio Age Height Family Husband Education Salary and Net Worth

Venezuela: A Living Tapestry Woven from Mountains, Ocean, and Millennia of Cultural Depth