What Is Sectionalism? The Divisive Root of America’s Political Fractures

What Is Sectionalism? The Divisive Root of America’s Political Fractures

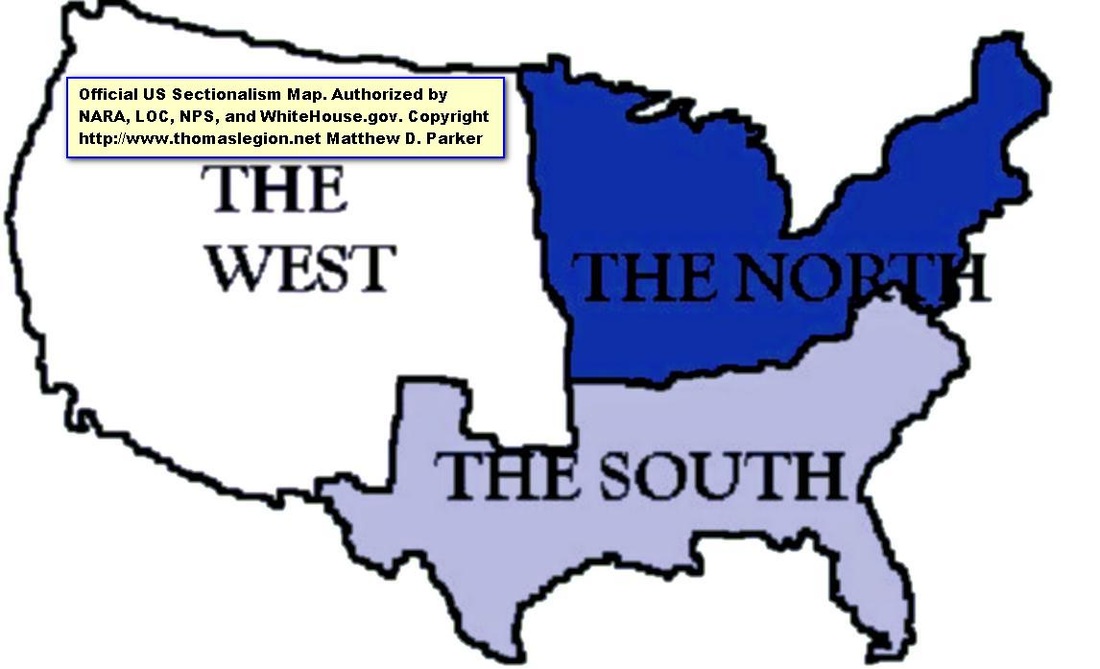

Sectionalism—the intense loyalty to regional identity over national unity—has profoundly shaped the United States since its founding, fueling political tension, economic conflict, and even violent rebellion. At its core, sectionalism reflects deeply rooted cultural, economic, and ideological differences that transformed the nation from a loose confederation into a fractured battleground. From the agrarian South’s defense of slavery to the industrial North’s drive for modernization, regional allegiances defined policy and politics, culminating in the defining crisis of the 19th century: the Civil War.

This phenomenon reveals not just historical divergences, but enduring fault lines in how Americans define identity, power, and shared destiny.

Sectionalism emerges whenever geographic, economic, and social differences align strongly enough to override national cohesion, fostering rival visions of governance and society. In the United States, this dynamic evolved through pivotal eras—from the foundational debates over slavery and federal power to industrial growth and westward expansion.

At its heart, sectionalism is more than regional pride: it is institutionalized loyalty to a region’s interests, often at the expense of national harmony. Historian Richard Hofstadter noted, “Sectionalism reveals the tension between local allegiance and national purpose—a friction that can neither be ignored nor fully resolved.” This tension crystallized in policy disputes, electoral politics, and ideological clashes that redefined American democracy.

Roots of Sectionalism: Geography, Economy, and Identity

The origins of American sectionalism lie in the nation’s uneven geographic and economic development.The North, with its dense population, navigable rivers, and emerging factories, gradually shifted toward industrialization, urban centers, and wage labor. By contrast, the South’s economy remained deeply tied to large-scale plantation agriculture—dominated by cotton, tobacco, and rice—relying fundamentally on enslaved labor. As historian David Potter observed, “The divergent economic systems created conflicting life ways: mechanized production in the North versus agrarian dependency in the South, each viewing federal power through a distinct lens.”

These structural differences seeded ideological divides.

In the North, reform movements like abolitionism gained momentum alongside moral opposition to slavery, while Southern elites fiercely defended their “Way of Life” as integral to sovereignty. The cotton boom intensified the South’s dependence on slavery, entrenching it not only as an economic system but a philosophical and political stance. This divergence transformed regional identities into political blocs.

Each section developed unique institutions, press narratives, and legislative priorities, creating feedback loops that reinforced allegiance to regional interests.

Sectionalism in Action: From Compromise to Conflict

The 19th century witnessed sectionalism escalate from political debate to outright confrontation. Landmark compromises—such as the Missouri Compromise (1820) and the Compromise of 1850—attempted to balance sectional power but ultimately delayed rather than resolved underlying tensions.Each measure revealed the difficulty of reconciling irreconcilable visions: while the North sought to limit slavery’s expansion to preserve moral and political equilibrium, the South demanded protection of their “property rights” as paramount.

Key flashpoints illustrate how sectionalism translated into political stalemate. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, by allowing popular sovereignty in new territories, reignited violent skirmishes—“Bleeding Kansas”—as pro- and anti-slavery settlers clashed in dramatic fashion.

The Dred Scott decision (1857), which denied citizenship to Black Americans and invalidated federal limits on slavery, deepened Southern confidence in judicial protection of their interests while galvanizing Northern resistance. Meanwhile, economic policies like tariffs or railroad development favored regional advantage—burnishing Northern industrial dominance while deepening Southern resentment over federal favoritism.

Sectionalism, Nullification, and the Road to Civil War

Sectionalism found its most radical expression in the doctrine of nullification, most starkly embodied by South Carolina’s 1832 response to the Tariff of Abominations.Under the leadership of John C. Calhoun, the state declared federal tariffs unconstitutional and refused compliance—a direct challenge to national authority. This crisis underscored a central truth: sectionalism, when coupled with constitutional skepticism, could undercut federal unity.

As Calhoun asserted, “The Union, no longer a compact of equals but a sovereignity divided, must either accommodate or be dissolved.”

The ensuing political crisis revealed how sectional loyalties could override compromise. While Congress temporarily defused the conflict with the Compromise Tariff of 1833, the underlying divide remained. Over the next decades, economic disparity, cultural alienation, and a failure to bridge irreconcilable values eroded trust.

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860—perceived by the South as a threat to slavery—triggered secession and theaping of national cohesion. By that point, sectionalism had festered not merely into politics, but into a moral and existential crisis that culminated in civil war.

Legacy and Lessons: Sectionalism Beyond the Civil War

Though the Civil War ended the physical conflict, its legacy of regional division endures in American political consciousness.Sectionalism did not vanish; instead, it adapted into new forms—regional voting patterns, debates over federal versus state power, and cultural divides still shape national discourse. Today’s partisan geography, with deep urban-rural and coastal-inland rifts, echoes historical fractures, revealing that identity and economic interest continue to realign allegiances.

Understanding what is sectionalism, then, is not merely an exercise in historical analysis—it is essential for navigating modern governance.

The lesson of history is clear: when regional loyalty eclipses national commitment, compromise becomes harder and unity more elusive. As scholars emphasize, “Sectionalism is not the enemy per se, but unbridled regionalism that undermines the nation’s capacity for collective action.” By examining the roots and evolution of this phenomenon, Americans gain clarity on both past struggles and present challenges, reinforcing the fragile but vital bond of shared citizenship. h3>Defining Sectionalism: More Than Regional Pride Sectionalism transcends mere affection for one’s home state or region.

It denotes a political and social allegiance strong enough to shape policy preferences, public sentiment, and institutional loyalty along geographic lines. Unlike simple regional pride, sectionalism often entails opposing views on fundamental values—especially around governance, economic systems, and fundamental rights like human dignity.

In the U.S.

context, sectionalism crystallized along North-South lines, driven by slavery, economic structure, and divergent visions of federal authority. Professor Michael Shellenberger notes, “Sectionalism transforms geography into an identity marker that overrides national unity.” Such divisions are not static; they evolve with historical context but retain a persistent power to fracture collective action.

Sectionalism’s Enduring Relevance in Modern Politics

Though slavery is no longer a legal reality, sectional dynamics persist in subtle, structural ways.Regional disparities in poverty, education, healthcare, and political representation echo 19th-century fault lines. Conservatives often associate certain states with traditional values, while progressive enclaves champion social reform—mirroring past cleavages, albeit refracted through contemporary issues like immigration, climate change, or healthcare.

Electoral maps today reflect deep geographic divisions.

The South’s enduring Republican dominance contrasts with the Northeast and West Coast’s Democratic strongholds. Patent examples include the South’s resistance to federal voting rights protections in the mid-20th century and today’s resistance to certain urban-centric policies. Polls show ticking red vs.

blue states are increasingly correlated with cultural and economic geography, not just demographics—proving regional identity remains a critical determinant of political behavior.

While modern coalition politics attempt to transcend hard regional divides, the underlying tension endures. Sectionalism, therefore, is not a relic but a recurring current in American democracy—a reminder that national unity requires constant negotiation between local pride and shared purpose.

The story of sectionalism reveals America’s most profound challenge: balancing diversity with unity. By understanding its origins, manifestations, and enduring influence, citizens and leaders alike confront a central truth—any nation’s strength depends not on erasing difference, but on fostering connection across it.

Related Post

The Rise of Collin Rugg: Analyzing the Digital Strategy and Influence of a Conservative Media Figure

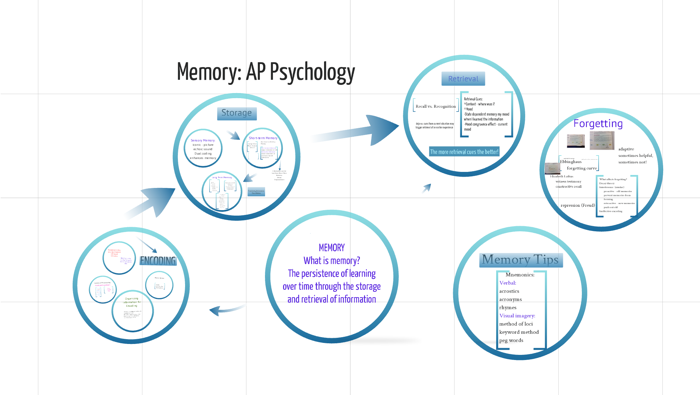

Prototypes Ap Psychology: The Memory Blueprints That Shape Our Thoughts

Dive into the Beat: Alan Walker MP3 Downloads & DJ Erycom’s Remix Revolution