What Is the Divine Right Theory? Unveiling the Sacred Foundation of Kingship

What Is the Divine Right Theory? Unveiling the Sacred Foundation of Kingship

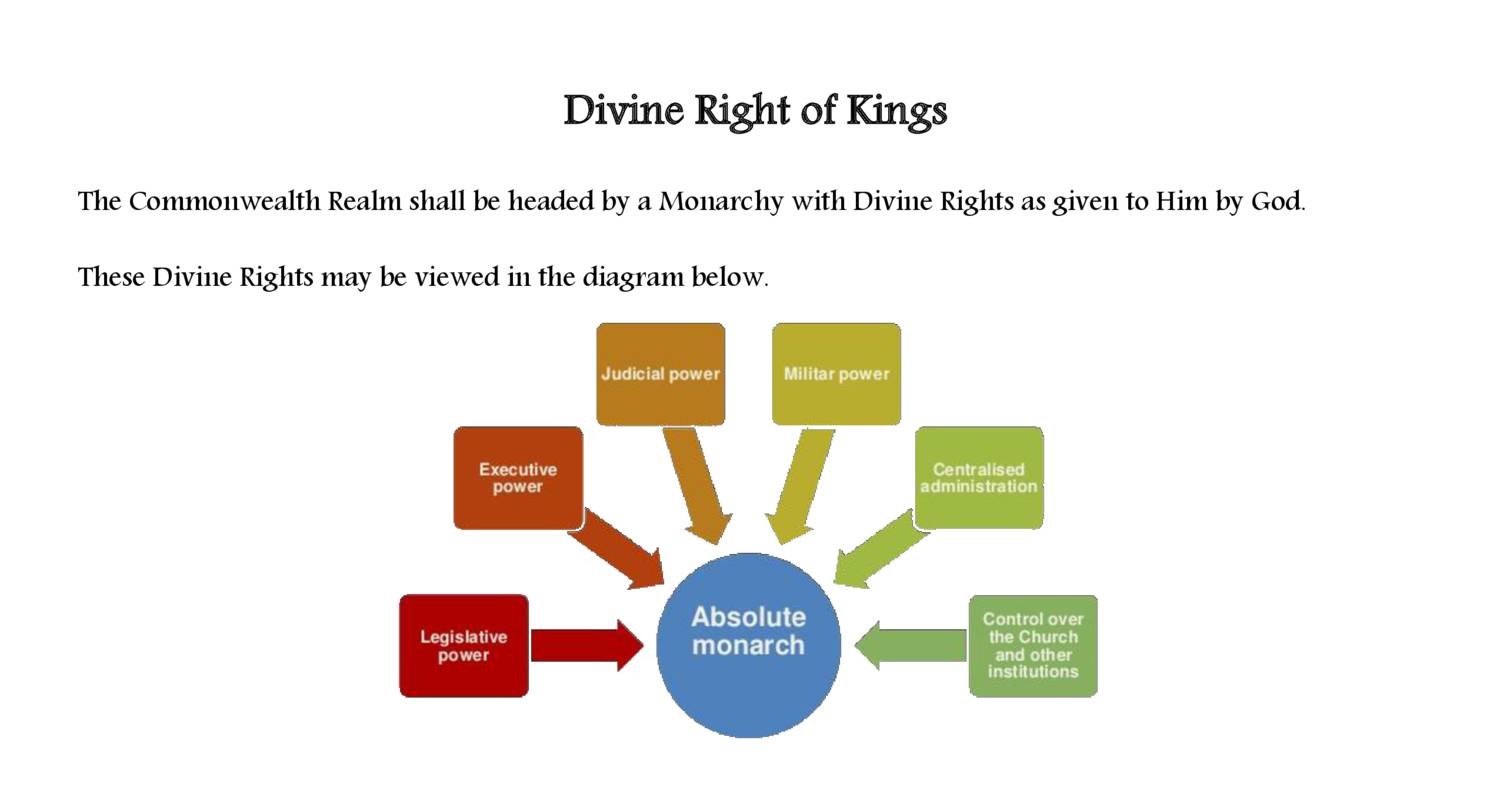

Stretching across centuries of European political thought, the Divine Right Theory stands as a powerful doctrine that once legitimized monarchy through celestial endorsement. It posited that a ruler’s authority derived not from human institutions, but directly from God—rendering kingship a sacred, unchallengeable order. This belief, deeply rooted in religious authority and political theology, shaped governance, fueled revolutions, and continues to inform discussions on power, sovereignty, and legitimacy.

Understanding what the Divine Right Theory truly meant reveals not only a medieval mindset but a critical chapter in the evolution of modern political philosophy. The core tenet of the Divine Right Theory is simple yet absolute: monarchs rule by divine appointment, answering only to a higher, sacred power. Unlike hereditary rule grounded in custom or contract, this theory framed kings as God’s appointed stewards, their decrees legally infallible because they emanated from divine will.

As political philosopher John Locke would later critique, such reasoning claimed to insulate rulers from earthly accountability—effectively placing monarchy beyond criticism or rebellion.

The Historical Roots: From God-Kings to Legitimacy

The origins of the Divine Right Theory weave through ancient theocracies and early Christian doctrine. Biblical precedents, such as the anointing of King David in the Old Testament, provided early templates—kings as chosen servants of God.Early Church thinkers, particularly from the 5th century onward, reinforced the idea that secular rulers derived authority through divine decree, not popular consent. Saints Augustine and later medieval theologians like Thomas Aquinas argued that political order served divine purpose, legitimizing rulers who upheld God’s will on Earth. By the 16th century, amid religious upheaval and rising monarchies, this doctrine evolved into a sharp political weapon.

European rulers—especially in England, France, and later absolutist states—embraced it to counter growing challenges to their power. Henry IV of France, whose reign ended decades of religious civil war, famously declared, “L’État, c’est moi” (“I am the state”), but earlier monarchs justified rule through the unassailable claim of divine sanction. In Protestant realms, the theory adapted to support divine approval regardless of esprit de napoléon, while Catholic monarchs emphasized papal blessing as part of the sacred endorsement.

The expression “divine right” itself crystallized during a period when theater and theology merged in statecraft. Monarchs staged elaborate ceremonies—coronations draped in religious symbolism—to dramatize their sacred authority. Churches preached that resisting the king was tantamount to resisting God, turning rebellion into theological heresy.

Such language elevated kingship from political office to divine mission, reshaping public perception across generations.

Key Proponents and Political Applications

King James I of England emerged as the theory’s most articulate defender. In works such as *The True Law of Free Monarchies* (1599) and *Basilikon Dominion* (1599), he argued that kings governed by God’s supreme authority, not by the consent of the governed.For James, “the king’s power is not of man, but of God,” and subjects were bound to obey because to defy meant defying divine will. This uncompromising stance earned legitimacy but bred tension, especially as English political thought grew more skeptical of unchecked rule. Louis XIV of France embodied the theory’s zenith in absolutism.

His reign (1643–1715) reflected a seamless fusion of crown and divine mission. The Sun King’s court at Versailles became a stage where monarchy was glorified as God’s earthly reflection. Religious propaganda and court rituals echoed James I’s vision, reinforcing the idea that the king’s word was lawmost.

Even rebuffing parliamentary challenges, Louis insisted, “L’État, c’est moi”—not as ego, but as divine mandate made flesh. Across Protestant and Catholic kingdoms alike, rulers invoked divine right to consolidate power during turbulent eras—wars, religious reforms, dynastic crises. Yet its application was uneven.

In England, the theory clashed brutally with Enlightenment ideals, helping fuel the 1688 Glorious Revolution. In France, it perpetuated decades of unchallenged despotism—until rebellion changed everything.

The theory’s strength lay in its ability to transform political rule into a transcendent truth.

But that very transcendence made it vulnerable to doubt and revolution. For centuries, bishops and ministers alike endorsed the idea that monarchs ruled by grace from heaven. Yet as secular thinkers questioned traditional authority, the sacred foundation of divine right crumbled under scrutiny.

The Decline and Drag The Divine Right Theory’s perceived triumph began unraveling in the 17th century, as political philosophy shifted from divine mandate to human consent. Thinkers like John Locke, in *Two Treatises of Government* (1689), directly challenged its core: if government derives authority from the people, then kings are not above rebellion but accountable stewards. Locke wrote, “the people… have a right to resist and absolutely to depose” illegitimate rulers—a radical break from divine absolutism.

Historical turning points accelerated its fall. The English Civil War (1642–1651) shattered the illusion of inviolable monarchy, culminating in Charles I’s execution and the temporary abolition of the crown. The Glorious Revolution (1688) seized this momentum, establishing constitutional monarchy in England with William and Mary induced to rule by parliamentary consent rather than divine decree.

Louis XIV’s France, though not democratized, later faced revolutionary upheaval in 1789—when poverty, inequality, and Enlightenment ideals combined to dismantle absolute rule. The theory’s legacy is not merely historical. Its collapse marked a pivotal shift: power increasingly derived from law, consent, and representation.

Yet remnants persist. Royal families today often invoke ceremonial “divine” symbolism—linking present legitimacy to sacred tradition—blending old reverence with modern governance.

Though divine right as a formal doctrine faded, its influence endures in political culture’s deeper questions: When is authority legitimate?

Who governs by right or choice? The divine right theory reminds us that the idea of monarchy was never just about power—it was about meaning, about weaving rule into something eternal and sacred. That fusion of politics and theology, for better or worse, shaped centuries of governance and still echoes in modern debates over sovereignty, faith, and the source of political legitimacy.

Related Post

Arena Do Gremio: Unveiling Total Capacity and Seating Excellence in Porto’s Iconic Stadium

Tokyo Revengers: The Essential Cast Behind the Grit of Död City’s Revengers

Brittany Murphy And Lili Reinhart: Two ascending Stars Whose Talents Eclipsed Early Promises

The Hidden Ladder Beneath the Nobility: Decoding Ranks Below Earl and Viscount