What Is the Number of Moons for Mercury? The Absolutely Empty Planet’s Moon Count Explained

What Is the Number of Moons for Mercury? The Absolutely Empty Planet’s Moon Count Explained

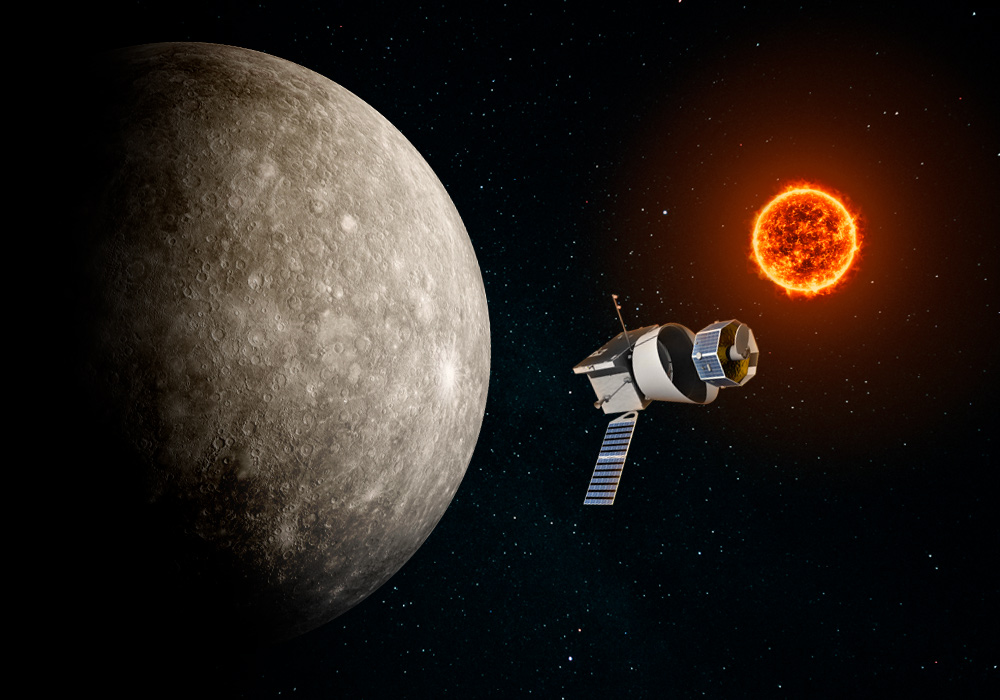

Mercury, the smallest and innermost planet in our solar system, stands apart not only for its extreme proximity to the Sun but also for being utterly devoid of natural satellites. Unlike gas giants or even Earth’s moon-rich neighborhood, Mercury does not possess a single orbitally bound moon, a fact rooted in its unique orbital dynamics and weak gravitational influence. Understanding why Mercury has no moons reveals critical insights into planetary formation, solar system evolution, and the delicate balance required for a body to capture and retain a satellite.

The Striking Absence: No Moons Orbiting Mercury

Despite decades of observation and advanced telescopic imaging—including from spacecraft such as NASA’s MESSENGER and ESA’s BepiColombo—Mercury remains one of the few planetary bodies in our solar system with no confirmed moons. The planet’s moon count is, in fact, precisely zero. This absence is not merely an unusual detail; it is a defining feature of Mercury’s physical and environmental environment.Curiously, while planets like Earth, Mars, and Jupiter boast dozens or even over 80 known moons, Mercury’s silence at the satellite level stands in stark contrast.

Why Mercury Has No Natural Satellites

The lack of moons around Mercury is anchored in several interrelated physical factors. First, Mercury’s extremely small size—just 4,880 kilometers in diameter, about 38% the radius of Earth—results in a weak gravitational field incapable of capturing or sustaining distant orbiting bodies.Its surface gravity measures only 3.7 meters per second squared, far below the threshold needed to hold a moon in stable orbit over billions of years. According to planetary scientist Dr. Jason Barnes of the University of Idaho, “Mercury’s gravity is too feeble to retain even a small moon, especially one vulnerable to solar perturbations.” Second, Mercury orbits within the Sun’s intense gravitational well and experiences powerful solar tidal forces.

These forces destabilize the orbits of any small bodies attempting to settle into stable lunar paths. Any potential satellite would either be pulled into the planet or flung away by the complex interplay of solar and planetary gravity. Third, the planet’s proximity to the Sun means its orbit lies within a region where gravitational disturbances from rotating solar plasma and radiation pressure are amplified, further discouraging moon formation or survival.

Mercury’s Position in the Solar System: A Satellite-Sparse Zona

Positioned in an orbital region close to the Sun, Mercury exists in what astronomers term the “ hardest gravitational zone” for satellite formation. Unlike the moons of gas giants, which may form from circumplanetary disks of gas and dust, rocky inner planets like Mercury lack extensive debris disks capable of coalescing into moons. The planet’s formation history—believed to involve a violent early bombardment phase—did not provide the extended reservoirs of material needed to birth natural satellites in its immediate vicinity.Moreover, Mercury’s lack of a substantial atmosphere translates to minimal atmospheric drag retention, which might otherwise influence small bodies entering its sphere of influence. Yet without a dense atmosphere (surface pressure less than 1% of Earth’s), no mechanism exists to slow approaching objects into orbit. Instead, meteoroids typically impact the surface directly or disintegrate harmlessly in the thin exosphere.

This environment compounds Mercury’s challenges in acquiring a moon.

Comparisons Across the Solar System: A Unique Case

Mercury’s moonless status stands in sharp relief when compared with other terrestrial and inner solar system bodies. Earth’s single moon, Mars’ two modest moons (Phobos and Deimos), and Mercury’s neighbors—Venus, with none, and Mars, with its two conglomerate moons—reflect a spectrum of satellite potential.The contrast becomes even more striking when considering that Mercury’s orbital zone is not gravitationally isolated; in contrast, asteroids in the region, like those in the asteroid belt, show no tendency toward moon acquisition, underscoring Mercury’s exceptional planetary classification. Planetary dynamist Dr. Emily Lakdawalla notes, “Mercury is an outlier.

Its empty moonscape reflects its harsh environment and unique gravitational constraints—factors that differ fundamentally from the moon-bearing worlds.”

The Role of Orbital Mechanics and Capture Failures

Even if Martian-sized fragments or passing debris occasionally approached Mercury, the planet’s orbital speed relative to potential satellites creates additional barriers. Moons typically form from orbiting debris that gradually accretes through collisions and gravitational clumping—processes hampered by Mercury’s limited gravity and fast orbital velocity. The planet completes an orbit every 87.7 Earth days, placing it in a swiftly moving environment where sustained orbital stability is difficult.As a result, any small moon would likely have either escaped, collided with the surface, or drifted away within geologically short timescales. Furthermore, tidal locking and orbital resonance—mechanisms that stabilize many satellite systems—are absent for Mercury’s hypothetical moons. Without resonant interactions to anchor and protect orbiting bodies, formations remain transient and unsustainable.

Evidence from Space Missions Confirms Zero Moons

Across multiple space missions, conclusive data have reinforced Mercury’s moonless existence. NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, which orbited Mercury from 2011 to 2015, imaged the surface repeatedly with no evidence of moons. Its high-resolution cameras found no orbiting objects passing through photographs with consistent trajectories, while radar and orbital tracking data conclusively ruled out even sizable satellites.Similarly, ESA’s BepiColombo mission, currently in orbit modeling, continues to observe Mercury’s environs without detecting any moon-sized bodies. These findings firmly establish the zero-moon count. Statistical models of inner solar system formation further support this conclusion.

Simulations indicate that terrestrial planet-forming zones close to the Sun, where Mercury resides, are unlikely to accumulate the mass and stability required for moon retention. Inward-migrating materials during planetary accretion were less likely to provide moon-forming debris, explaining the rarity of satellites around inner planets.

Mercurian silence in the moonscape is not a fluke or oversight—it is the cumulative result of physics, orbital mechanics, and formation history.

With zero confirmed satellites, Mercury stands as a clear example of a planet shaped by extreme gravitational and thermal forces that prevent the birth or survival of natural moons. This singular trait enriches our understanding of planetary diversity and the conditions necessary for satellite systems. For astronomers and planetary scientists, Mercury offers both a puzzle and a boundary case—illuminating the limits of moon formation in our solar system’s inner realm.

Though Mercury lacks moons, its surface bears scars of ancient impacts and planetary evolution,

Related Post

Watch Indian Serials With English Subtitles Online: Your Gateway to Uninterrupted Storytelling

How Old Are The Backstreet Boys in 2024? Their Age Spans Reveal a Legacy Waiting to Age

Ed Sheeran reveals eerie last phone call with Australian Cricketer Shane Warne